Journal of Young Researchers № 5 July 2017

Abstract

Experience from developed countries suggests that as child protection is concerned, professional social workers have a leading role to play in ensuring that quality services are available to vulnerable children and families.

After more than 20 years of ratifying CRC and initiating child care system reform, Georgia and other countries of CEE/CIS region succeeded in introducing social work profession. However, until now it lacks required professional functions and capacities.

The below findings are derived from 2015 inventory consolidating information about social work workforce (SWW) from 21 countries and territories of the region, ranging from high to low income countries. The inventory illustrates diversity of the social work workforce framework and its composition, recognizing a variety of functions, levels of education and regulation in both governmental and non-governmental workforce. Findings capture basic elements specific to certain systems and also identify some common challenges and trends evident across locations.

For the SWW to be effective, it should be well organized and supported to address all essential roles of social work practice and ensure continuity of their provision across the sectors and settings. Proposed inter-connected intervention areas are critical for achieving this goal.

Key Words: Social Work Workforce; Child Protection; Professional Functions and Capacities; Challenges; Interventions

რეზიუმე

განვითარებული ქვეყნების გამოცდილება ამტკიცებს, რომ ბავშვთა დაცვის სფეროში, მოწყვლადი ბავშვებისა და ოჯახებისთვის საჭირო მომსახურებების მიწოდებაში წამყვანი როლი სოციალურ მუშაკებს აკისრიათ.

გაეროს ბავშვის უფლებათა კონვენციის რატიფიცირებისა და ბავშვთა კეთილდღეობის სისტემის რეფორმის დაწყებიდან თითქმის 20 წლის შემდეგ, საქართველოში და ცენტრალური და აღმოსავლეთ ევროპისა და დამოუკიდებელ სახელმწიფოთა თანამეგობრობის რეგიონის სხვა ქვეყნებში, დაინერგა და გარკვეულწილად განვითარდა სოციალური მუშაკის პროფესია. თუმცა, დღემდე ეს სფერო განიცდის პროფესიული ფუნქციებისა და უნარების მწვავე ნაკლებობას.

წარმოდგენილი მონაცემები ეყრდნობა 2015 წელს რეგიონის 21 ქვეყანასა და ტერიტორიაზე ჩატარებულ გამოკითხვას. გამოკითხვის შედეგები ცხადჰყოფს, თუ რამდენად განსხვავებულია ქვეყნებში აღიარებული სოციალური მუშაკის ფუნქციები, განათლების დონე, ლიცენზირების მოთხოვნები და ზოგადად, მარეგულირებელი ჩარჩო. ასევე ნაჩვენებია ცალკეული სისტემებისთვის დამახასიათებელი ელემენტები, საერთო ტენდენციები და გამოწვევები.

სოციალური მუშაობის ეფექტურობისთვის, მნიშვნელოვანია ქვეყანაში არსებობდეს კარგად ორგანიზებული სისტემა, რომელიც უზრუნველყოფს სხვადასხვა სექტორებში სოციალური მუშაობის წამყვანი ფუნცქიების შეუფერხებელ და ხარისხიან გახორციელებას. შემოთავაზებული ინტერვენციები მნიშვნელოვან როლს ითამაშებს ამგვარი სისტემის ფუნქციონირების დონის გაზრდაში.

საკვანძო სიტყვები: სოციალური მუშაობა; ბავშვთა დაცვა; პროფესიული ფუნცქიები და უნარები; გამოწვევეი; ინტერვენციები

Introduction

The Convention on the Rights of the Child states that “the child, for the full and harmonious development of his or her personality, should grow up in a family environment” and that the “state parties shall ensure that a child shall not be separated from his or her parents against their will unless this is necessary for the best interests of the child” (CRC, 1989).

In order to meet these standards the States need to put in place child care systems comprised of a set of laws, policies, regulations, services, capacities, monitoring and oversight needed across all social sectors to prevent and respond to protection related risks. Creation of a protective environment for all, requires the state authorities to develop and support families, with particular emphasis on the most vulnerable. However, largely due to the legacy inherited from the socialist regime, the state systems in Georgia, as many other countries of Central Eastern Europe and Commonwealth of Independent States (CEE/CIS)[1] Region had weak structures, were heavily relying on institutional care, did not provide alternative services for children deprived of parental care and were lacking state programs meeting individual needs of the vulnerable children and families (UNICEF, 2011). A majority of children in formal care had one or two living parents and only a very small proportion was separated from their families because of a violence and deprivation of parental rights (EveryChild, 2005). The main reasons of institutionalization were limited capacities of families to provide care for their children resulting from poverty, domestic violence, health conditions of children or parents, personal crises and emergencies affecting the household (EuroChild, 2013).

Existing systems were failing to prevent family separation due to the lack of the required structures, services and professionals able to ensure holistic approach and emphasise importance of family strengthening. In most of the countries of the region one of the key components of a functional child care system - social work profession did not exist at all (Greenberg and Partskhaladze, 2014).

Following the ratification of the Convention on the Rights of the Child in early 1990s, Georgia and most of other countries in CEE/CIS Regions became involved in diverse reform initiatives. As a result of a growing understanding of the negative impact of residential care on child development and well-being and recognition of the critical importance of the family, the initial aim of the reforms was defined as deinstitutionalization of residential institutions. Later on, it has transformed into wider strategies of child care system reform and family strengthening (Greenberg and Partskhaladze, 2014).

The new requirements for the national child care systems informed by CRC and the UN Guidelines for the Alternative Care of Children strongly emphasized the importance of a family support and social work services in preventing separation of children and empowering vulnerable families with necessary capacities to care for their children (Partskhaladze, 2016).

As a result of advocacy and support of many international and local organizations, and efforts made by the national government, Georgia and several other countries in the region have achieved progress in reducing rate of residential care and strengthening other components of child care system. Countries have introduced or reestablished social work profession and training programs. Though many challenges still persist. Inability of a system to reach out and support the most vulnerable children, who are consistently left behind and provide them with needed services is one of the key issues. Children with disabilities, members of ethnic minorities (Roma children in particular), children living in rural areas continue to be overrepresented in the institutions and display significant gaps in the realization of their rights (UNICEF, 2011). Hence, child care systems, still under development in most of the countries, need to strengthen focus on the most marginalized and improve outreach to these groups, in order to reduce equity gaps. .

Experience from developed countries and countries in the region indicates, that social work workforce is central for outreaching to the most in-need groups and development of individualized and systemic approach to child protection. Insofar as child protection is concerned, professional social workers with specialist skills to outreach, identify and respond to child protection concerns according to policies, procedures, and care standards have a leading role to play in ensuring that services are available to vulnerable children and families. The emphasis of a child care reform on a holistic approach targeting complex needs of children and families and engaging overlapping systems, further increased an importance of a well-planned, well-trained, supported social work workforce able to address existing needs (Better Care Network and Global Social Service Workforce Alliance, 2014).

However, to be an effective agent of a change in a reforming child care system, social work required well defined professional mandate, requisite powers to make important decisions in a child’s life, an authority that must be accompanied by a duty to protect and the practical and theoretical knowledge to undertake assigned roles. According to the Framework for Strengthening the Social Service Workforce, key strategies for achieving these results are “planning the workforce,” “developing the workforce,” and ‘supporting the workforce” (Global Social Service Workforce Alliance, 2016). Despite ongoing efforts, after about 20 years of ratifying CRC and initiating child care system reforms, Georgia and most of the other countries in CEE/CIS region lag behind in implementing these strategies and hence, lack social work capacities fundamental for the reforms.

Literature Review

By definition, social service workforce is a formal or informal, paid or unpaid, governmental and non-governmental, qualified and unqualified workforce, contributing to promoting the social rights and ensuring the care, support, and protection of the most disadvantaged children, families and other vulnerable groups in different settings in order to reduce equity gaps (Better Care Network, 2014).

As needs and circumstances in the countries are diverse, as are ongoing developments in different sectors utilizing social work workforce at the national and local levels, this workforce includes a wide range of skilled or unskilled workers, namely social worker, child and youth care worker, community development worker, Roma mediator, outreach worker, social work assistant, social assistants, para-social workers, probation officer, etc. One of the largest sub-groups of this workforce is social work, which is a focus of this paper.

According to the latest definition approved by the International Federation of Social Workers (IFSW) in 2014 “social work is a practice-based profession and an academic discipline that promotes social change and development, social cohesion, and the empowerment and liberation of people. Principles of social justice, human rights, collective responsibility and respect for diversities are central to social work. Underpinned by theories of social work, social sciences, humanities and indigenous knowledge, social work engages people and structures to address life challenges and enhance wellbeing. The above definition may be amplified at national and/or regional levels” (IFSW, 2014).

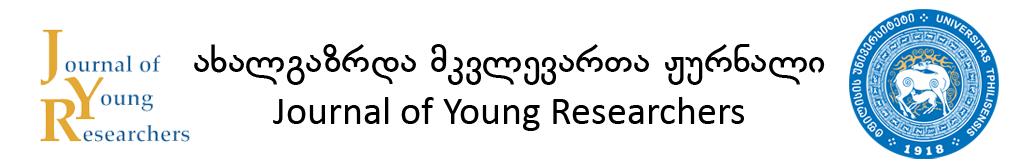

For the social work workforce to meet the needs of children and families with diverse personal circumstances, life situations and needs in child protection and other areas, it is mandatory to put in place well organized and supported continuum of social work functions. In well-developed systems the continuum includes below analysed, sometimes overlapping roles, considered as important for ensuring holistic approach to the needs of children and families. Listed functions put into practice a global definition of the profession. They are well-illustrated on the example innovative and successful practices from CEE/CIS countries aiming to prevent infant abandonment and summarised in a Compendium of Promising Practices developed by the UNICEF Regional Office for CEE/CIS (UNICEF, 2015).

1. Outreach and early identification is an effective approach for reaching out to the most vulnerable groups, otherwise not able to receive needed support. Outreach services can be provided by different groups of social service workforce, as well as by aligned professionals (i.e. outreach workers, home visitors, etc.), however it is critical to have social workers assigned a stronger mandate in this area. Currently in all countries of the region, particularly the countries with poorly developed social work, outreach functions are insufficiently developed and performed. Hence, the poorest and the most marginalized children and families are invisible for child care system and are not able to receive needed support.

In regards to the impotence and effectiveness of outreach work, the Compendium provides examples from Bulgaria, which had highest rated of institutionalization of children under the age three in the region. In order to strengthen outreach and support the most vulnerable families in one of the regions of the country, Bulgaria modelled a work the municipal Family Centres responsible for providing social, health and educational services and supporting small children and families at risk. Through strengthened outreach, during the period of two years the Centres have identified more than 2500 families from disadvantaged communities, who were supported in obtaining needed services. Over 90 per cent of these families had never accessed existing social services before. Strengthened outreach and support prevented abandonment of 103 children, also reducing the placement of infants in the regional Infant Home by 90 per cent. Social workers identified 250 unregistered pregnant women, previously excluded from the health system, who were provided with support during the pregnancy, childbirth and the postnatal period. Through improved outreach, social workers have identified hundreds of children who were not attending kindergartens, have dropped out of education system or have not received compulsory vaccinations, and supported them in receiving needed healthcare and education services.

2. Counselling and provision of information is another key social work function enabling vulnerable children and families to be aware about their rights, available resources and procedures required for obtaining them. Through counselling and informing clients about the health and social protection programs, training and employment opportunities, family planning and positive parenting skills, family support services and a wide variety of other topics, social workers are able to enhance independence and empower vulnerable families for making informed decisions and right choices.

The Compendium provides an example from the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (tfYROM), when strengthening of counselling services, provided by social and health workers at the maternity hospitals helped pregnant women and mothers of the new-borns (particularly young, single, homeless women) in overcoming critical periods and preventing risks of child abandonment.

3. Prevention focused social work practice has a growing priority in the field of child care. Prevention is the most effective approach for ensuring positive outcomes for children and their families, as well as the way of reducing the need for more expensive specialist services. Dominance of a reactive approach and a lack of preventive services and interventions, able to help families in crisis has been one of the key reasons for high institutionalization rates in the region and other issues pertinent to child care system.

Taking into account the magnitude of child relinquishment and abandonment in medical units, introducing preventive social work services in healthcare facilities has proved to be effective in many countries of the region. In Romania newly introduced social workers in maternity hospitals provided counselling for mothers, assisted them in obtaining identity documents for themselves and their children; provided information and facilitated access to family planning or family physician services; connected the families to community resources; provided general counselling and emotional support to the mothers and other members of a family in order to strengthen mother-child bonding and, when relevant, remove barriers to the acceptance of the child. Combined with other interventions, mainstreaming preventive social work model into national programmes and policies significantly contributed to reducing child relinquishment and abandonment in maternity units and paediatric hospitals (from 5,130 cases in 2003 to 1,474 cases in 2012 (71 per cent).

4. Service delivery and linking with other services is another well-recognized function of social work practice continuum. It entails delivery of generalist or sector-specific interventions to address the needs of children and families. Depending on the level and character of needs, support services can be provided within or outside the families and communities, by qualified or para-professional social work workforce. In case of need, informed and timely referrals to the professionals within or outside the sector are also considered as an important social work role.

Referrals, particularly referrals of abuse and neglect cased require particular attention and formalization through the referral protocols. Besides referring to services, social work functions also entail advocacy and support in claiming needed assistance, which is yet another highly demanded social work role in a resource-constraint and rigid child care system.

5. Social work role in Gatekeeping has been increasing in the region and aims at supporting at risk children and families in receiving support services and preventing unnecessary family separation. Effective gatekeeping entails many components, including effective functioning of the designated decision making entities, availability of a range of support services, assessment and information management systems, etc. However, social workers play leading role in ensuring effective gatekeeping. Introduction of social work roles in the maternity wards, polyclinics, family planning centres, as well as the entities making decisions about formal care placement has strengthened gatekeeping and improved functioning of child care system in some countries of the region.

6. While majority of formal social work roles in this region emphasise individual approach, community social work alsodeserves significant attention. Informal support from the communities and extended families have often been complementing or substituting for a lacking state support in many locations through the region and hence, better understanding of these resources and capitalization on the existing assets should become a more widely practiced role for social work. Besides, community development approaches can be crucial in empowering disadvantaged communities, raising awareness of child protection issues, and strengthening community mechanisms for improving child well-being.

7. Social work Case Management is a method of assessing, planning, coordinating, advocating and monitoring complex cases. Due to the diverse needs of children and families and the importance of the holistic, client centred approach, case management entails close coordination with other services and professional teamwork within and outside the organization, hence requiring recognition of social work mandate and professional boundaries. A case management approach also involved partnership with families in defining the needs and working toward the set goal. In most of the countries of the region, case management is poorly developed and practiced, though several countries (i.e. Armenia) are attempting to operationalize provision of integrated social service (ISS) by applying case management methodology.

8. Protection and safeguarding, entails complex interventions to be performed by social workers and other professionals in order to prevent and respond to child maltreatment. Nowadays, it is increasingly recognized that home visitation services provided by nurses, social workers or other professionals represent a unique opportunity to identify violence, abuse and neglect and strengthen parenting skills and resources. However, when facing a situation of child abuse and neglect, statutory social work role of safeguarding a child is unavoidable. Even though often ignored and left behind the closed doors of the families, schools and institutions, social workers should be capably and authorised to remove a child from unsafe environment and provide other support for a child victim.

9. Monitoring, evaluation and recording client progress a final, and at the same time ongoing step of the continuum. It is an important way of maintaining the focus on the needs and circumstances of children and families and ensuring that termination of work does not take place before achieving set outcomes and is not caused by a lack of resources or a desire of the agency to close a case.

In order to ensure that social work workforce has needed capacity for performing above listed functions, the countries of the region which are still searching for the country-specific solutions, should ensure that workforce strengthening is considered “in the context of a larger systems framework that links to and reinforces other components of the social service system, including legislative and policy environments, leadership and governance structures, coordination and networking mechanisms with other key sectors and communities, financial systems, and information management services” (Global Social Service Workforce Alliance, 2016, pg. 7).

A number of indicators designed by the UNICEF East Asia and Pacific Regional Office and USAID MEASURE Evaluation project for measuring the outcomes of social service system strengthening, are analysed in CEE/CIS context in a section below.

|

MEASURE Evaluation– Future Social Service Workforce Strengthening Indicators for PEPFAR Programs for Orphans and Vulnerable Children Existence of a national regulatory framework for social service workforce Existence of a national regulatory body for social service workforce Availability of social service workforce data Existence of a national strategic plan on strengthening the social service workforce Existence of a national professional association for social service practitioners Number of certified social service workers, by cadre Number of registered social service workers, by cadre Ratio of social service workers with responsibility for child welfare per total child population Vacancy rates of government social service workforce positions, by cadre UNICEF East Asia and Pacific Regional Office Indicators- Human Resources Child Protection Regulation of requirements and standards for social work professionals Professional training for personnel working on child protection service delivery Government’s capacity to attract qualified child protection professionals Government’s capacity to retain qualified child protection professionals Diligence of staff working on child protection Overall size of civil service/public sector staff with responsibility for child protection Human resources dedicated to children and justice Source: (Global Social Service Workforce Alliance) |

Findings

The below findings are derived from the inventory consolidating information about the social work workforce (SSW) from 20 countries and territories in the CEE/CIS region, ranging from high to low income countries. The inventory was conducted in 2015 and aimed to analyse the key social service workforce data (or highlight its lack) and development trends in order to contribute to the advocacy efforts for strengthening SSW and consequently, supporting vulnerably children and families. The inventory illustrates the diversity of the social work and social service workforce framework and its composition, recognizing the variety of functions, levels of education and training and regulation in both governmental and non-governmental workforce. Findings capture basic elements specific to certain systems and also identify some common challenges and trends evident across locations.

The rapid assessment inventory included open and close ended questions structured around three key areas, namely Current Workforce, Regulatory Framework and Social Work Education. To collect basic information, the questionnaire was disseminated to a network of local professionals from 21 countries of the region working in the field of child protection and social work by e-mail. One country did not provide inputs. To further clarify received answers, conference calls/focus groups were organized with the professionals representing four sub-groups (i.e. Sub-group 1: Bosnia and Herzegovina, Albania, Macedonia, Montenegro, Sub-group 2: Bulgaria, Romania, Croatia, Sub-group 3: Armenia, Georgia, Sub-group 4: Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Azerbaijan, Kosovo, Belarus).

It is important to highlight the limitations of the rapid assessment. Currently no country in the region, has a clearly identified body that is tasked with gathering SSW data. Few countries have systems to collect uniform data on social service human resources, including their functions and workload. Hence, this inventory was envisioned as an initial step to be followed with more in-depth quantitative and qualitative research on the development trends, achievement and challenges in the field of social work in the Region.

For the purposes of this exercise, the following inclusive term was used to define social service workforce: formal, paid, governmental and non-governmental, qualified and unqualified workers presently represented in the workforce and contributing to promoting the social rights and ensuring the care, support, and protection of children and other vulnerable groups in different settings. Professional and para-professionals under this title could be called by different names in different countries, including but not limited to social workers, para-social workers, social assistants, child and youth care workers, community development workers, probation officers, etc.

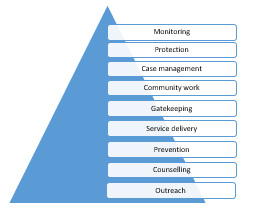

The questionnaire provides information about the deployment of social work workforce in different fields, namely child welfare, justice, education, health/mental health, etc. According to the responses from 20 countries, all but three countries (including Georgia) employ child welfare social workers. Further exploration is needed to define reasons and bottlenecks prohibiting introduction of statutory social work function in these countries (two upper-middle-income and two lower-middle-income country).

Depending on the countries territorial organization, child welfare social workers are employed at the central or local levels. In addition, countries have governmental and non-governmental social workers employed in the fields of juvenile justice, aging, education, healthcare, mental health, etc. Countries identified SWW (with working titles of social workers, peer educators, social agents, probation officers, psychologists, school police inspectors, primary health care social workers, etc. ) also working with the victims of domestic violence, persons with disabilities, children in alternative care services and residential institutions, youth infected with HIV, persons affected with TB, etc.

In half of the countries child welfare social work function is centralized (or deconcentrated, like in Georgia), while in the rest of the countries statutory social work function is decentralized. Majority of the countries report having social workers working with older persons at the central and/or local government entities. After the child welfare social work, this is the second most widespread field of social work in the region and potentially can be better used for identifying the needs of other members of the family (children, persons with special needs, etc.).

In Georgia, the process of developing social work profession was linked with the initiation of child protection system reform. The process marked with the adoption of a law on Foster Care in 1999 and hiring and training 18 persons as child care social workers in 2000 (Doel et al, 2016). The initiative, which was launched collaboratively by the Government of Georgia, UNICEF and the British Charity Organization Every Child aimed to support deinstitutionalization of 90 out of 5300 children placed in 46 state-run residential institutions (Partskhaladze, 2016). The success of a project resulted in the institutionalization of the social work profession in a number of sectors, but maintained strong emphasis on child protection social work (Shatberashvili, 2016).

Another trigger for the development of the profession was the establishment of the Social Services Agency (SSA) in 2005. This state agency, responsible for of administration of all social services in the country currently employs up to 250 social workers, available in all 69 municipalities of the country. Even though SSA is a largest employer of social workers in the country, all stakeholders in the field consider exiting social work cadre to be inadequately small for meeting needs and properly performing basic social work functions.

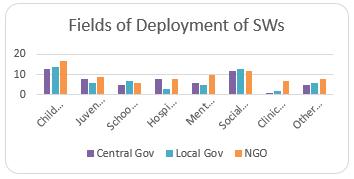

One of the challenges, also identified though the rapid assessment is a lack of standard qualification requirements for the social workers in almost one half of the countries (including Georgia)

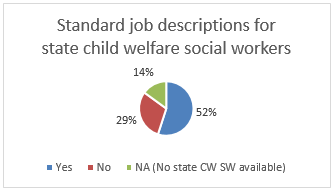

In 70% of the cases, availability of the standard qualification requirements coincides with the existence of standard job descriptions for the state child welfare social workers, which are put in place in more than a half of the countries. In some countries having no standard job descriptions, social services in general are regulated by different state orders, while in others, no regulations are in place, thus significantly challenging quality assurance possibilities.

Georgia is among the countries with no standard qualification requirements for social workers. Child welfare social workers have standard job descriptions, outlining accountability for more than 25 areas related to children, older persons and persons with disabilities.

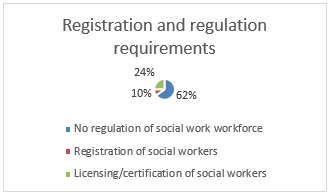

Analysis also shows that majority of the countries (mostly the states and territories of the former Yugoslav Republic) having in place standard qualification requirements and standard job descriptions of the child welfare social workers, are also advanced in regulating social work through registration or licensing and have uniform legal definition of the profession. Unfortunately, despite long-term efforts of the Georgian Association of Social Workers (GASW) and many other key actors, the issues of social work workforce registration and licensing, qualification requirements, professional standards and many more are still unresolved in Georgia.

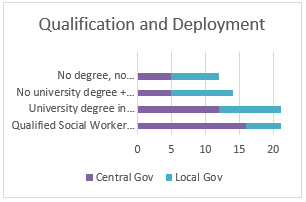

As countries have no clear-cut qualification requirements for social workers, deployment of the state child welfare social workers is also very diverse. In some countries social work workforce is represented only by qualified social workers; in others (like in Georgia) by qualified social workers and professionals with the university degree in other fields, retrained as social workers. In the third group of countries, the level of qualification of SSW ranges from qualified staff to the personnel with no university degree and no training in social work.

The countries in the region do not have clearly identified body that is tasked with gathering SSW data, including their caseload. Only few countries possess information about the existing average workload (number of active cases) of the state child welfare social workers. Based on the received information the workload of the social workers ranges from 150 to 2 active cases, with data mostly lacking for the urban and rural locations outside the capital. Data suggests that in Georgia an average workload of the state child welfare social workers in Tbilisi is around 88 cases.

Regulating caseload of social workers and employing adequate number of staff is another important factor affecting the quality of their performance. This is particularly true in the remote locations, where outreach work and family visits (if/when performed) are very demanding due to the long distance and lack of transportation means.

Information collected about coverage of state child welfare social work services is vague in most of the countries. Some of the countries report to have nationwide coverage exclusively through the central governmental entities and/or municipal entities; others have partial coverage through the central or municipal entities; while as noted above, some countries report not to have the state child welfare social work available at any level. This fact makes child care system reform goals difficult/impossible to, as the lack of statutory social work functions is an equivalent of not having effective gatekeeping mechanisms, individual needs assessment, planning and monitoring, family support, etc.

As noted above, in Georgia SSA employs social workers in every municipality of the country. However, due to the low numbers, the national coverage does not translate into an easy access to social work services.

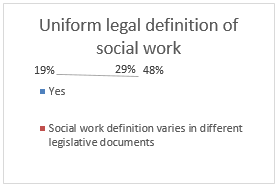

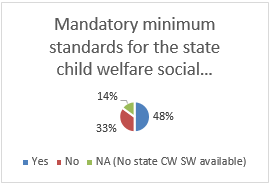

The inventory looks into the legal definitions of social work, as well as the existence of the minimum standards for the state child welfare social workers. Responses from the countries indicate that in one half of the countries’ social work is legally defined and child welfare social work is regulated by the mandatory standards, while in the second half, social work has no legal definition or the definition varies in different legal documents and performance of social workers is not guided by the minimum standard requirements.

The lack of the legal definition of social work mandate and its registration/regulation requirements (especially for the statutory social workers) is a significant challenge for the field of child protection, as it limits authority of social workers and prohibits the state from ensuring appropriate quality of social work interventions. It also makes difficult to have an effective role distribution in the social service workforce and creates gaps and overlaps in the provision of certain functions.

Varied legal definition of social work functions and mandate also creates challenges in building effective referral system between the social workers employed in different areas (i.e. justice, education, healthcare, child welfare, etc.) and similarly causes fragmentation in service provision to the most vulnerable children and families.

Georgia belongs to a group of countries where social work does not have one overarching legal definition. Aassessments conducted in Georgia by Hollis, Shatberashvili, Rutgers University Center for International Social Work research team, Doel et al., report that different pieces of legislation define the roles and functions of social work in specialized areas differently (i.e. the Law on Social Assistance, 2006; the Law on Adoption and Foster Care, 2007; the Law on Domestic Violence, 2010; the Law of Psychiatric Assistance, 2009, etc.).

Georgian legislation recognized social work as a profession in 2006. According to the Law of Georgia on Social Assistance, responsible for this recognition, a social worker as a person equipped with the special responsibilities by the guardianship and custody institution. Several additional laws provide a definition of social work as it relates to the specific needs of the field. The existence of multiple laws and diversity of used definitions gives a feeling of fragmentation and allows for wide interpretation of a profession, ranging from basic unskilled work through to professionals offering specific forms of social support.

Inventory also indicates that countries with longer history of social work development apply licensing/certification requirements to the social work workforce or at least register social workers. Georgia does not belong to this group of countries.

Evidence from different countries in and outside the region shows that authorisation for registering or licensing social workers can be entitled by the state to the designated state agencies of outsources to the non-state entities. Outsourcing of licensing and/or registration function can play an important role in overcoming challenges existing in some countries due to the limited capacity of the state agencies, their restricted flexibility, higher cost and lower quality of service provision, etc.

Social work academic education level and continuing education requirements (often encompassed in licensing requirements) are also diverse in the countries of the region. One country reports not having academic (BA, MSW, PhD), vocational or certificate trainings in social work. Three countries have academic education at the undergraduate level, while others have two or three level education in social work.

Georgia succeeded in establishing social work academic programs in three local universities, training professional social workers at undergraduate, graduate and doctoral levels since 2006.

After receiving professional education and/or being employed, social workers are offered or are obliged to engage in continuing education in 50% of the countries. In countries with no continuing education requirements, like Georgia trainings offered to the social workers are often project driven or ad hoc and do not always respond to the needs of the social workers.

Discussion

For the social work workforce to be effective, it should be well organized and supported to address all essential roles of social work practice and ensure continuity of their provision across the sectors and settings. Proposed four inter-connected areas, equally important for ensuring effective implementation of all core social work roles discussed above, aim to address identified challenges in the field.

Objective 1 – Knowledge Generation and Exchange

Analysis of developments and challenges in social work and how they affect realization of children’s rights builds strong foundation for effective response. Knowledge about the bottlenecks in the provision of social work roles, in particular the outreach, referral, case management and other functions will enable authorities and other key stakeholders in ensuring effective planning at the regional, country and local levels. At the same time, analysis of available resources and promising practices will facilitate effective knowledge exchange opportunities across the countries.

Objective 2 – Enhance Legal and Policy Framework

Complex political and administrative environment and lack of national-level legislation and policies related to social work, hinders implementation of social work roles (especially statutory functions) in many countries. At the same time, inconsistence in the application of the existing policies and laws aggravates inequality between the children and families living in diverse locations and circumstances through the countries, as they are not able to receive standardized and quality services. Objective 2 aims suggests to identify existing and lacking social work roles and elaborate the evidence based national legislation and policies for ensuring uniform provision of quality services by the professional and para-professional social workers. Strengthened legal and policy framework also aims to facilitate effective inter-sectoral collaboration, requiring clearly outlines protocols and lines of responsibilities, ensuring holistic response to the needs of at risk children.

Objective 3 – Strengthening of Institutional Environment

To be effective in implementing their core roles, practice effectively and ethically, social workers need a working environment that upholds ethical practice and is committed to standards and good quality services. Employing agencies need to have a clear understanding and written policies outlining the roles, workload, quality assurance mechanisms and methodologies of performing social work functions. Manageable workload and fair compensation, defined based on the local context, ongoing support and supervision of social workers, are guarantee for ensuring protection of children and families. In the countries with shorter history of social work, promoting consistent understanding about the roles and functions of social workers among the authorities, general public and employing agencies will also help in building a healthy foundation for the profession and ensure desired quality of social work roles.

Objective 4 – Social Work Education and Capacity Building

Knowledge and skills of social workers employed to perform diverse functions at different levels in the state and non-state entities, largely determine effectiveness of their interventions and outcomes for children and families. Introduction and strengthening of academic and continuing education system, based on the international practice and education standards, is the key building block for ensuring capacitation and empowerment of social work professionals. Development of the aligned education system will also help the countries in preventing fragmentation and reducing costs of the overlapping ad hoc training efforts. In the process of strengthening education system, special attention should be made on inter-sectoral competencies of social workers and incentive system for supporting their deployment in hard to reach communities.

When considering these and other actions necessary for strengthening social work service workforce, it is of a critical importance for the countries to take into account the needs and developments outside the child protection field as well. Evidence suggests that social work workforce development is relevant for developing effective system of social protection and integrated social services, healthcare and home visitation programs, early learning and school readiness, education and many more.

References

- Better Care Network and Global Social Service Workforce Alliance (2014). Working Paper on the Role of Social Service Workforce Development in care reform. Washington, DC: IntraHealth International.

- Child Protection Hub for South East Europe (2016). The Social Service Workforce as Related to Child Protection in Southeast Europe: A Regional Overview. Terre des hommes

- Doel, M. Kachkachishvili, I., Lucas, J., Namicheishvili, S., and Partskhaladze, N. (2016). Book Chapter – Creating Social Work Education in Georgia. International Handbook of Social Work Education, pp. 96-106. Routledge

- EuroChild (2013). Family and Parenting Support in Challenging Times. Eurochild, Brussels

- EveryChild (2005). Family Matters: A Study of Institutional Childcare in Central and Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union. EveryChild, London

- Global Social Service Workforce Alliance (2016). Review of Legislation and Policies that Support the Social Service Workforce in Low- and Middle- Income Countries

- Global Social Service Workforce Alliance (2016). The State of the Social Service Workforce 2015 Report. A Multi-country Review. Washington, DC: IntraHealth International.

- Greenberg, A. and Partskhaladze, N. (2014). How the Republic of Georgia has nearly Eliminated the Use of Institutional Care for Children. Infant Mental Health Journal. Vol. 35, Issue 2, pg 185-191

- Hollis, C. (2008). Evidence-based assessment of social work practice in Georgia. UNICEF.

- International Federation of Social Workers (2014). Retrieved from http://ifsw.org/get-involved/global-definition-of-social-work/ on 6 April 2016.

- Partskhaladze, N. (2016). Quality of Life of Deinstitutionalized Children as an Outcome Measure of the Child Care System Reform in Georgia. Journal of Young Researchers, Iv. Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University. Retrieved from http://jyr.tsu.ge/index.php/Hoome/ebaut/eng/ on 5 April 2016.

- Rutgers University Center for International Social Work (2008). Social Work Education and the Practice Environment in Europe and Eurasia. USAID Social Transition Team, Office of Democracy, Governance and Social Transition

- Shatberashvili, N. (2011). Social Work Situation Analysis. Georgian Association of Social Workers

- Shatberashvili, N. (2016). The Poverty Reduction Program in Georgia: A Social Work Perspective. Doctoral dissertation

- UNICEF (2011). End Placing Children under three Years in Institutions. A Call for Action. UNICEF CEE/CIS RO

- UNICEF (2015). Compendium of promising practices to ensure that children under the age of three grow up in a safe and supportive family environment. UNICEF Regional Office for Central and Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States, Geneva

- UNICEF (2015). Evaluation of Results Achieved through Child Care System Reform 2005-2012 in Georgia. Pluriconsult Evaluation Report

- United Nations (2010). Guidelines for the Alternative Care of Children. Retrieved from https://www.unicef.org/protection/alternative_care_Guidelines-English.pdf on 7 December 2016

- United Nations (2010). Guidelines for the Alternative Care of Children. Retrieved from https://www.unicef.org/protection/alternative_care_Guidelines-English.pdf on 7 December 2016

- United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989). Retrieved from https://www.unicef.org/crc/ on 9 January 2017

- United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989). Retrieved from https://www.unicef.org/crc/ on 9 January 2017

- USAID (2008). Social work education and the Practice environment in Europe and Eurasia. Rutgers University Centre for International Social Work

[1] According to the United Nations Children’s Fund, CEE/CIS Region includes Albania, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kosovo (under UNSC Resolution 1244), Kyrgyzstan, the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Montenegro, Republic of Moldova, Romania, Serbia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, Uzbekistan.