Journal of Young Researchers № 3 July 2016

რეზიუმე

სტატია აანალიზებს 1920-იანი წლების საბჭოთა კინოში ახალი საბჭოთა ქალის მოდელს. 1917 წლის რევოლუციის შემდეგ ახალი საბჭოთა სახელმწიფოს მიზანი იყო ახალი საბჭოთა მოქალაქეების შექმნა. „ახალი კაცისგან“ განსხვავებით, „ახალი ქალი“ მრავალი კამათისა და წინააღმდეგობის საგანი იყო. ეს გამოწვეული იყო იმ გარემოებით, რომ ახალი საბჭოთა ქალის ცნება კულტურულად მიღებული ფემინური იდეალის ხელახალ განსაზღვრებას მოითხოვდა: იგი თავდადებული აქტივისტი და დამოუკიდებელი ქალი უნდა ყოფილიყო. მიმდინარე დისკუსია მოიცავდა არა მხოლოდ ქალთა ცხოვრების წესის, არამედ მათი გარეგნობის, ფიზიკური აღნაგობისა და ტანსაცმელის განხილვასაც კი. სტატია იკვლევს, თუ რა შინაგანი წინააღმდეგობები ახასიათებდა ამ დისკურსს და აანალიზებს ახალი საბჭოთა ქალის სახეს მიხეილ ჭიაურელის მხატვრულ ფილმში ,,საბა” (რომელიც ერთადერთია სახკინმრეწვის მიერ 1920-იან წლებში გამოშვებულ ფილმებში, რომელიც ასახავს თანამედროვე ყოფას ქალაქში) და განიხილავს მას უფრო ვრცელ კონტექსტში. ზოგად კონტექსტუალიზაციაში იკვეთება რომ ახალი საბჭოთა ქალის დისკურსით ხდებოდა არა ფემინურობის პოზიტიური რედეფინაცია, არამედ განკაცების წინ წამოწევა: მიუხედავად ძლიერი, აქტიური ქალის დამაჯერებელი რეპრეზენტაციისა, ,,საბა”-ში ფემინურობა კვლავ კოდირებულია როგორც სუსტი და პასიური, ხოლო სიძლიერე და აგენტობა განსაზღვრულია როგორც მასკულინური.

საკვანძო სიტყვები: ქალთა რეპრეზენტაცია, მუნჯი კინო, ახალი საბჭოთა ქალი.

Abstract

The aim of the article is to explore the New Soviet Woman model in 1920s Soviet cinematic representations, particularly in Georgian context. After 1917 revolution the new Soviet State aimed to create New Soviet citizens. Contrary to New Soviet Man, the New Soviet Woman was a question of many debates and controversies. This was caused by the fact that New So-viet Woman insisted on redefinition of culturally accepted feminine ideal: New woman was supposed to be an ardent activist and independent woman. The ongoing debate besides women’s living mores also included their looks, both in terms of physi-cal appearance and clothes. The article investigates the contradictions within the New Woman discourse, and analyzes the representation of a New Soviet Woman in Mikheil Chiaureli’s Saba (the only Georgian film produced in the 1920s decade representing modern women) and situates it into a wider context. The overall contextualization reveals that the discourse of a Soviet woman did not redefine femininity in positive terms, but advanced immasculation: In Saba, regardless the persuasive representation of a strong, active woman, feminine is still encoded as weak and passive, whereas the strength and agency is defined as masculine.

Keywords: women’s representation, silent cinema, New Soviet Woman,

Introduction

The Bolshevik revolution aimed to create a completely new structure: a socialist state inhabited with new kind of people. As historian Peter Kenez notes Bolsheviks “did not merely want to control the govern-ment, right wrongs and eliminate abuses; they aimed to build a new society on the basis of rational prin-ciples and in the process to transform human nature and create the new socialist human being” (Kenez 2001, p. 26). Regardless the audacious spirit and enthusiasm such radical transformation of mostly agri-cultural Russia (and other Soviet republics were no different), inhabited by vast number of illiterate popu-lation, was hardly a manageable task. The revolutionaries founded their optimism on a very existence of a new medium: cinema, which they viewed as a very powerful tool to communicate with and enlighten illit-erate masses in order to accomplish their goals of society’s transformation. Lenin’s quote “the cinema is most important of all arts” (Taylor & Christie, 1994, p. 57) was so frequently cited and repeated both by party officials and press that became an actual slogan. Lenin and other Bolsheviks regarded cinema not because of its artistic potential, neither they could predict or sense the emergence of great soviet filmmakers in upcoming years that would not only bring international fame to the Soviet cinematography but also crucially influenced the filmmaking in general, but because they saw it as the most appropriate educative tool for the illiterate masses. Use of propaganda films seemed the easiest way to explain the revolution and educate population politically. In Soviet society cinema had multiple functions, which alongside such a major mission as the propaganda of the Bolshevik system and consciousness, also combined other “minor” tasks, which had “economic, educational, artistic and social aspects” (Rimberg, 1973, p. 39). The films were teaching and educating masses not only about political ideals, ideology and history but included everything that had to do with very much elementary activities, like how to eat, how to take care of hygiene, how to cross the street, etc. (Hochmuth & Bulgakowa, 2008). Cinema was ex-pected to function as a weapon of soviet society’s transformation, for creation of new soviet human be-ings. New Soviet Man and the New Soviet Woman were “two totemic figures,” obsession with which, to put it in Lynne Attwood’s and Catriona Kelly’s words, was “one of the most characteristic features of the Soviet society in the 1920s and 1930s” (Attwood & Kelly, 1998, p. 256).

In the case of New Soviet Man it was easy; it was clear that he had to be “a highly moral, socialist paragon of virtue, dedicated to the final goal of communism” (Miller, 2010, p. 13), whereas the case of the New Soviet Woman was far more complicated. Obviously, she also had to embody all these characteristics, but this was not all. Contrary to the New Soviet Man, who fits in the accepted masculinity (strong, muscu-lar, etc.), the New Soviet Woman required redefinition of femininity. Bolsheviks were very well conscious about women’s oppression and supported their emancipation, which meant, putting it in Alexandra Kollontai’s words, turning “the self-centered, narrow-minded, and politically backward baba”- a female fig-ure considered to be illiterate and superstitious, into “an equal, a fighter and a comrade” (Wood, 1997, p. 1). The Bolshevik government made steps to ameliorate women’s condition: they facilitated divorce pro-cedure, mandated equal rights and equal pay for women (although to what extent all these steps worked in reality in favor of women, and their controversial effects, is already a topic for a different paper). They even created a special women’s section- Zhenodtel, responsible for work among women. Concept of “work among women” meant to reach out other women, to spread information about the new socialist state and women’s rights in this state at nonparty meetings and to persuade regular female residents that cooperating with the state would have far more advantages, rather resisting it. All these issues, constitut-ing „the woman question” were widely and intensively discussed and women’s body was “a site for con-siderable contestations” (Grant, 2013, p. 72). The image of woman and the ideology of women’s equality were used and modified by the soviet authorities in order to assure homologation for economic and de-mographic policy changes (Grant, 2013). Nikolai Korolev, a “respected doctor, with some influence”, in 1924 “discussed the ‘complete and unconditional emancipation’ of women following the revolution and now they were viewed as being on an equal playing-field as men. The New woman, like her male counter-part, was strong, healthy and cultured” (Grant, 2013, p.74). But to what extent should a woman have been emancipated, be it on physical or social level? There was no unanimous answer to this question. Korolev had even designed three categories of female bodies: prerevolutionary ideal who was “poorly developed, with a long neck, narrow, sloping shoulders, a short torso, narrow pelvis and skinny legs,” whose primary physical function was to be attractive to men; a “Tsarist times peasant housewife” with short neck, over developed-waist, prominent pelvis, long torso and short legs; and the third, ideal of the New Soviet Wom-an, who was in between these two. But it must be mentioned that Korolev still situated the emancipated Soviet woman in a domestic realm, and stressed her reproductive function (Grant, 2013). As Susan Grant remarks “while the state espoused female emancipation and equality between sexes, women’s liberation was in fact ostensibly undermined and inhibited by the alleged physical, emotional and psychological disposition of women themselves” (Grant, 2013, p. 76). Despite the right of abortion, it was disapproved, the motherhood was still ideologically stressed and films often depicted economically and individually independent New woman, who either already was, or was about to become a mother, but she did not need a biological father when there was a state to take care of her and her child (Attwood, 1993). These representations varied, of course, but in Russian films it was a trend.

Nothing much can be said about the representation of New Soviet Woman in Georgian soviet silent films because contrary to Moscow productions, focusing on contemporary life, provinces (Leningrad, Ukraine and Georgia) were producing films situated in the past (Rist, 1925). It was not until the very end of the decade when Georgia’s State Cinema Production offered films depicting contemporary life. Mikheil Chiaureli’s Saba, (filmed in 1929) is the only film of Georgia’s State Cinema Production, which is situated in a modern city and represents modern citizens: New Soviet Man and New Soviet Woman respectively. It centers on a city tramway driver Saba, who is addicted to alcohol and depicts his rehabilitation or, to put it in Oksana Bulgakowa’s words (when she talks about the trends in films produced during this time), rep-resents the cure of damaged “raw human material, necessary to create a New man” (Hochmuth & Bul-gakowa, 2008, 1: 04:17). This cure also includes restoration of the damaged cell in the Soviet society’s organism - a worker’s family, and exposes meanwhile the tension between public and private realms. Po-sitioning the public and private realms is interesting to explore in many ways, but this time I will only dis-cuss it briefly in terms that it is a female role model, who personifies the public realm on a symbolic level. On the example of Saba, I will examine what kind of New Woman’s model was offered to Georgian audi-ences, using cinematic language analysis and situating this representation in a wider discourse using dis-course analysis. By discourse analysis I mean examining the contemporary official discourse -newspaper reports and articles describing model of New Soviet Woman and comparing women’s representation in Saba both to historical data and other cinematic representations.

Contextualizing Saba

Saba was filmed during the Cultural Revolution, taking place in the course of Stalin’s five-year plan in 1928-1932. The Cultural Revolution, a Bolshevist version of Enlightenment, aimed to transform the Soviet Union population and to construct a New Soviet Man and a New Soviet Woman respectively. The con-cept of “Cultural Revolution” was first voiced by V. I. Lenin. In Peter Kenez’s words, what Lenin meant when he spoke of the need of Cultural Revolution, was a “desperate need to catch up with the industrial and advanced West, and to overcome the dreadful weight of Russian backwardness,” stating immediately that Lenin’s successors had something “very different” in mind while using this term: “In this period [late twenties] cultural revolution represented a resurgence of utopian notions about the culture and politics and a demand for complete break with the past” (Kenez, 2001, p. 92). This implied the rejection of cultural pluralism existing during early twenties, as well as modifying and eradicating some types of daily behav-iors and rituals that were inevitable in the epoch of rapid industrialization and forced collectivization. The Union needed a different pulse and life rhythm. Excessive alcohol consumption, very much characteristic of the working class, was one of these rituals that the Bolsheviks saw as “one of the most troublesome and intractable aspects of…prerevolutionary working-class culture” (Transchel, 2006, p. 6). The slogans “Alcohol is our class enemy” and “enemy of the cultural revolution” were widely cited in the press.

Cinema was expected to function as a weapon of soviet society’s transformation, and compete and eventually replace two long-established lifestyle components in Russia that is the church and the tavern. It was Lev Trotsky who started to speak about the application of cinema in this respect in 1923: in an arti-cle published in Pravda, titled “Vodka, The Church and Cinema,” he declared that cinema could success-fully fight against alcoholism, persistent in Russian society, as well as against the church influence. In his opinion, cinema was “an instrument which we must secure at all costs” and that would be a great compet-itor for the public houses and churches equally (Taylor & Christie, 1994, p. 96). Stalin also echoed this idea in his Political Report in December 1927, stating that “it shall be possible to begin the elimination of vodka, by replacing it with such sources of income as the radio and the film” (Rimberg, 1973, p. 43). Lenin too was quoted to have said that it was only art that could substitute religion (Rimberg, 1973). These slo-gans became very often cited, echoed and repeated in the Soviet press. One caricature in Kino was even depicting the soviet cinematography as Saint George, holding a movie camera instead of a sword and a flag with inscription “Soviet Cinematography” as a lance; killing the dragon - alcohol (Fig. 1.).

Fig. 1

By the end of the decade “Cinema instead of Alcohol” became one of the most frequently repeated slo-gans in the Soviet press. In order to eliminate alcoholism the party was using various methods that be-sides the press propaganda included other means such as: delivering lectures, staging plays, arranging mock trials, agitational films, writing short stories and poems; a number of anti-alcoholic films were also released by collaboration of Narkomzdrav (People’s Commissariat for Health Care) and Sovkino (State Committee for Cinematography) (Rimberg, 1973). It must be mentioned that alcoholism was not such an inherent problem for Georgian population (more extensively on this issue see below) as it was in Russia. Nevertheless, in the mid-late twenties the Georgian journals and newspapers (Komunisti [The Com-munist], Mshromeli qali [The Working Woman]) were also actively carrying an anti-alcoholic campaign. Mikheil Chiaureli’s Saba, a release of Georgia’s State Cinema Production aimed to expose the dark sides of alcohol consumption and inspire the working class to give it up. Chiaureli grasped the “hot” theme in various perspectives: following the All-Union Party Conference on Cinema, held on March 15-21, 1928, the Georgia’s State Cinema Production elaborated a thematic plan that would allow the authors to take a proper pace in order to avoid the waste of the author’s energy on “not appropriate” themes. These themes, among exposing lives of modern intelligentsia, modern mountaineers’ life and the lives of Young Communist League members, included also the depiction of a modern city worker’s life (Amirghanov, 1928). Even if the plot centers on a rehabilitation of “damaged raw material” and a tension between public and private realms in this process, Saba is the first film, which shows emancipated woman. While discuss-ing it, I intend to examine what type of the New Soviet Woman was offered to Georgian audiences in the end of 1920s.

Saba has been always characterized as an “anti-alcoholism” film, but I would argue that actually it is more an “anti-domestic violence” film. Even if alcoholism was not an issue in Georgia(a), this was not the case with domestic violence. The numerous letters and special propaganda short stories published in Mshromeli qali, testimony to it. In the script plot, domestic violence is obviously connected to excessive drinking: it exposes a city worker’s domestic scene, and the society’s (party’s) effort to eliminate the pro-tagonist’s alcoholism eliminates the cases of domestic violence as well. In other words the film does not represent the domestic violence as a problem existing apart from alcoholism. Such coupling implies that domestic violence cannot subsist in a worker’s family on its own right, if the worker is not corrupted by an “enemy of socialism”, which is alcohol in this case. The intervention of public realm’s representatives into private household obviously creates a tension between these two spaces, which is dramatically exposed in the film. Whereas it is tempting to discuss Saba in these terms, as these are those major lines compos-ing the filmic narrative, my interest here is to examine and explore what kind of representation a New So-viet Woman is provided in the film, and how she functions in the film’s textual system rather than to inves-tigate the tension between public and private realms in the late-twenties soviet society. Although expos-ing such a sensitive theme as domestic violence, I have to emphasize once again, the film does not cen-ter on female characters, and it’s a man whose moral savior is in the focus of its development.

The original scenario for Saba was written by Sh. Alkhazishvili and A. Aravski. As already noted above, it depicts a story of a Tbilisi tramway driver Saba, who is addicted to alcohol and cannot help but waste all his monthly salary on drinks with his friends. When drunk he becomes violent and beats his young son, Vakthang (a pioneer gifted with engineering skills) and wife Veriko. Due to drinking and frequent scandals at home, first he is fired from work, and later Veriko, with the encouragement of the Young Pioneers leader Olgha, who is an agent of public realm divorces Saba. The latter becomes more desperate, until he (drunk) accidentally does not hit his own son. This tragic incident is followed by Saba’s public trial. The court hall is decorated with anti-alcoholic posters and placards, one of them, hanged in the center reads: “Alcohol is enemy of Cultural Revolution”. The workers judge Saba’s life, and when the representatives of factory committee claim that “today we must try not only Saba, but the whole old world, alcohol is our class enemy, which ruins millions of people” (as voiced by the narrator), the case is generalized and it is clear that alcohol stands as a signifier of all the old-time evil. The lawyer defends him, but also the whole community takes Saba’s side: his coworkers, who state that not only Saba has to be tried, but the whole collective, Veriko and head-bandaged Vakhtang (they appear unexpectedly during the trial). When, after giving a speech in front of judges Veriko rushes to Saba and gives him Vakhtang to hug, all the trial at-tendees also rush towards him, and it is not only Saba who hugs Vakghtang and Veriko, but the whole community.

The film ends with the Pioneers’ demonstration against alcohol. The demonstration is very much theatri-cal: pioneers are carrying a coffin, where a bottle of wine is placed, and also alcohol damning messages posters and placards. Olgha is giving a fierce speech, as well as other young pioneers including Vakhtang, who demonstratively shakes his banded injured arm. Saba is approvingly looking at the demonstration from the tram, and sees Vakthang who holds a postcard “Father, do not drink”. The gazes of future (that is Vakhtang) and of present once corrupted by the past (Saba) meet each other: the human damaged mate-rial is rehabilitated, cured and functional.

Public and Private

Saba deals with and reveals something more complicated than the mere fact of the restoration of the alcohol-damaged human material and a creation of a New Man per se. What is more interesting, in my opinion, is not the fact of having achieved a result (a New Soviet Man) but the processes: how and through which strategies it is achieved. Further, hand in hand with alcoholism, the film reveals and expos-es the household life scene that is also damaged by domestic violence, which (according to the plot) does not exist in its own terms, but is caused by alcohol and drunkenness. Via this direct link between alcohol and domestic violence, the film exposes how domestic violence is dealt by society that witness it, although without naming it as separate a problem: Saba is always blamed for drinking.

The witnessing audience is something to keep in the consideration during Saba’s analysis, which is espe-cially interesting in terms of positioning the public and private realms. Alexandra Kollontai was arguing for the liberation from private closed familial system, that was considered as bourgeois and for creation of an open communal space, where there would be no division between “mine” and “yours”, and everyone would pay attention with conscious awareness that these children belong to the community, first of all to the Bolshevik society; therefore, all the members were equally responsible for them (Kollontai, 1921). The party did worry not only about its workers’ public activities, that is providing jobs and ideological educa-tion, but also “with its all effort was looking after the improvement of workers’ private and familial condi-tions” as well (Burdzenidze, 1972, p. 93), which logically meant imposing certain surveillance on their private realms in order to ensure that their social and private behaviors were appropriate for “a truly Soviet working class” (Transchel, 2006, p. 100). Of course, domestic violence was inappropriate and it was also an issue to be eliminated from worker’s families. Friedrich Elmer’s Fragment of an Empire, produced the same year, was also addressing it among other problems (including working class drinking as well) pre-sent in the soviet society (Youngblood, 1992). Mshromeli qali was publishing thematic short stories, whose subject varied year after year according to current problems: emancipation of the oppressed pre-revolutionary woman, obligatory removal of burqas in Muslim communities, hypocrisy of men activists who were advocating Cultural Revolution and women’s emancipation, etc. In 1926, the whole range of the stories where dedicated to the description how a woman delegate or otherwise party activist with high Bolshevik consciousness liberates an oppressed woman from domestic violence and helps her to get aliment from a verbally and/or physically abusive, unfaithful husband. Correspondents’ letters, sent from various regions, were mentioning the productive work of women delegates, stating that now hus-bands are afraid to oppress their wives like in previous times, because they know that wives’ conditions are monitored by women delegates.The journal also offered juridical advices/information. Intrusion of party activists into workers and peasants’ family life, into their private space, obviously brings to the lime-light the notion of public/private dichotomy and the tension existing between them.

Hannah Arendt in The Human Condition distinguishes two types of the “public”, which are interconnected but nevertheless differ from each other (Arendt, 1998). The first is everything that is visible and hearable for everyone - things and facts on public display that create our reality. The second signifies the “world itself”, a place where we all belong and occupy our places, from which we see things differently, from our own perspective: a common world. As Arendt illustrates metaphorically, “To live together in the world means essentially that a world of things is between those who have it in common, as a table is located between those who sit around it; the world, like every in-between, relates and separates men at the same time” (Arendt, 1998, p. 52). This “common world” is constituted by various pluralisms, eradication of which equally disrupts it. As Arendt argues, the distinction of public and private realms matches the distinction between what should be hidden and what should be shown. It is just the same as the distinction between political and household realms, which in between have an amorphous social (since the modern ages), which is neither public nor private “strictly speaking”. Even if in a family circle everyone occupies different places and the perception of certain events is also seen from its members’ different and multiplied per-spectives, still it can never match to the perception from those different perspectives that emerge in the public realm. But the common world (the public realm) ends when in mass societies or during mass hys-teria “all people suddenly behave as though they were members of one family, each multiplying and pro-longing the perspective of his neighbor”; when pluralisms are eradicated and facts and things are seen “only under one aspect and is permitted to present itself in only one perspective” (Arendt, 1998, p. 58). According to Arendt, such confusion is the end of both: public and private realms.

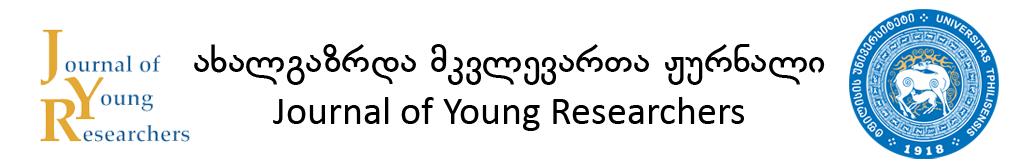

Public and private spheres in the Soviet society, which intended to create one “super-human family” (to use Arendt’s concept for what we call society), political organization of which in the Soviet case would constitute not a nation but a unification of different nations (an extended super-human family in a sense) were crucial factors. Walter Benjamin, who visited Moscow from late 1926 to early 1927, upon his return to Berlin wrote an essay “Moscow” where he stated that “Bolshevism has abolished private life” (Berhstein, 2006, p. 220). One of the basic factors in the process of putting private (household) space on public played the housing shortages, a characteristic problem of the Soviet Union and the communal livings. It turned impossible to distinguish private from public and practically obliged everyone to witness and participate in each other’s private lives. I noted above (and I will discuss it in details below) that pub-lic realm is personified in Olgha. But the public realm manifests itself at two instances: firstly, when neigh-bors are witnessing domestic violence, the balconies are overcrowded and they are looking at it as at a spectacle (Fig.5, Fig. 6) and secondly, at Saba’s trial. The family’s private life is on public display and, and the very fact of being on display nolens volens insists on public realm’s intervention. After just mentioned fight Veriko and Vakhtang spent the night sleeping on the stairs even if neighbors know they could not go home or elsewhere. Aware of living conditions in the early Soviet Union, the viewer is not surprised and does not wonder why no one offered a sleeping corner to the mother and child. Maybe a will of dramati-zation has its share, but the familiar audience knows that neighbors physically could not provide them with a free sleeping space. Here the housing shortage is present, although not articulated as a problem in the film.

Fig. 5

Fig. 6

Second time when public real manifests itself, is on Saba’s trial. Actually this trial is a culmination, which shows that there is no distinction between these two realms. The idea of super human family (Arendt’s concept of society, as mentioned above) is vividly expressed in the final court scene, when Veriko and Vakhtang reunite not only with Saba but also with the whole audience, as they approach and hug them too, creating a close circle around them: it is not a reunion of a private concrete family, but the reunion and celebration of Saba’s return to the public, state family (Fig. 7).

Fig.7

Besides these two scenes, the public realm is manifested through Olgha’s character: she functions as public realm’s agent who intervenes into the workers private space and tries to solve the problem. In a way she embodies a mother of the super-human family.

New Soviet Woman

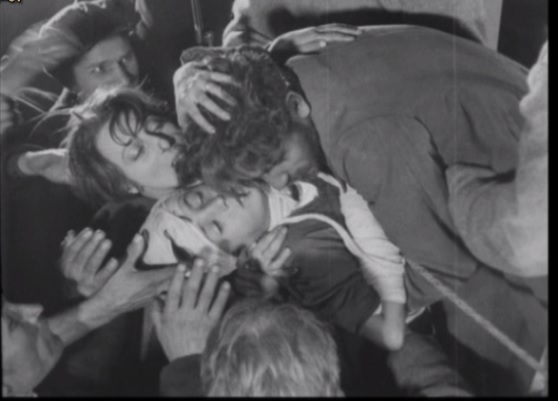

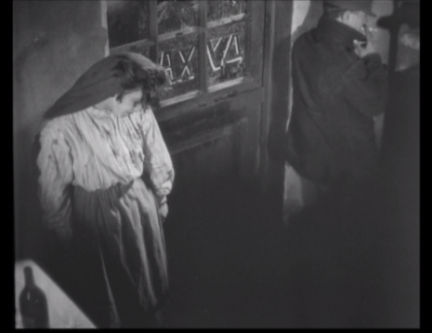

In the film there are two main female characters: Saba’s wife, Veriko, who experiences physical violence whenever he is drunk, an actor situated in a private realm, and a Young Pioneer Leader Olgha, who is an agent of the public realm and intervenes into a pioneer’s family when she sees Vakthang beaten and finds out the reason. But as already known from the plot synopsis above, this intervention does not bring result immediately. Quite contrary, it takes a range of public realm’s interventions into private one and at differ-ent stances to achieve the desired outcome --the cure of the damaged human raw material. But it is Ol-gha, who personifies the public realm, as she is the only public agent that we see acting throughout the plot emphasizing women’s active social role in the society. When Olgha goes to talk to Saba, Veriko wel-comes her: she is really eager and supportive of the public agent’s intervention in her private domestic scene, as Veriko is unable to handle it all alone and definitely needs help. It is especially interesting to ob-serve the contrast between these two women: contrary to heroines of other films, produced before Saba, they are no more differentiated by social hierarchy - both of them are modern working class women. The modernity is expressed here in such a simple marker as haircut: they both have the same short hairstyle. But this is the only trait alongside the class belonging that they have in common. In earlier film plots, women of the same class were generally embodying the similar characteristics, and were placed at the same position in terms of power relations determined by their class. Contrary to this, in Saba we see two female figures who belong to the same class, but regardless this factor they stand on different poles of power position/agency: whereas Veriko is weak, Olgha is strong. This weakness/strength also finds an expression in their looks: Olgha has masculine features - her physical construction is more robust and rough, corresponding to the emancipated woman’s bodily shape designed by Korolev, while Veriko is tender and slim, fitting in the prerevolutionary beauty standards. The camera position and body language also reveal their power full/less position in the filmic narrative: during the conversation Olgha is shown from the low angle medium shot, using phallic gestures (as described by Oksana Bulgakowa (Hochmuth & Bulgakowa, 2008) while analyzing variations of body language in Soviet films) emphasizing her power-fulness and authority, which belong to the masculine, in the masculine-feminine binary system (Fig.8). On the contrary, Veriko is shown from the high angle close up that indicates to her powerless and oppressed condition and exposes feminine passivity (Fig. 9). When waiting for Saba, two women are shown within the same frame in multiple shots followed one by another: Olgha is in the front plan, with strengthened back, reading something, whereas Veriko is on the second plan, shriveled with her head hanging (Fig. 10). The waiting for Saba scene lasts for fifteen seconds, but nothing changes much (Fig. 11, Fig. 12): Olgha remains in the front plan, rigid and concentrated on the newspaper, that is public life and social activity, and Veriko remains in the same powerless oppressed position, either with her head hanging or desperate-ly staring in the space. But this time the intervention of the public agent into private sphere is fruitless: the news that Saba has been fired from work, does not leave the space for further discussion.

Fig.8

Fig.9

Fig.10

Fig. 11

Fig. 12

Another day, when Saba hears how Olgha (who has developed a close relationship with Vakhtang and Veriko meanwhile) encourages Veriko to divorce, another sequence of violence erupts, which this time also includes Olgha as a target and consequently ends up with the trial and divorce.

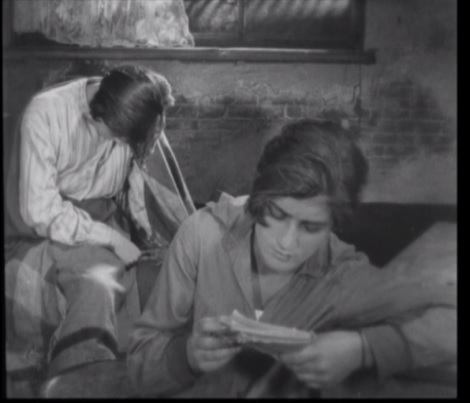

Even though the film shows how the collective, public realm saves Saba, it is not only Saba, who needs to be saved in the film. First of all, it is Veriko, a “damsel in distress.” Her “damsel in distress”- vulnerable and powerless position is depicted in a cinematic language: the camera mostly shows her from high angle when she is alone in the frame, or covered face (for example, in the tavern scene, after domestic violence has publicly taken place. Fig. 13, Fig. 14, Fig. 15) and in the court, when she defends Saba, indicating that she needs the

Fig.13

Fig.14

Fig.15

Fig.16

community’s assistance for help, holding her hand towards the court as if she asks for savior from drown-ing (Fig.16). Veriko, before final reunion of the collective family, is saved not by some “knightly” man, but by Olgha with her assistance, encouragement and support: after the first visit, Olgha frequently comes to Vakhtang and Veriko, and on the divorce trial she is sitting next to her, representing her interests, creating an example of women’s solidarity and backing. Olgha is an androgynous agent of the public realm. Be-sides her apparent masculine features and powerful gestures, she also manifests caring -a feature of motherliness: it is with her intervention that the problem is eradicated from the domestic scene and she does it because she cares for Vakthang. In the ideological climate where motherhood was vividly stressed, and often represented as a way of liberation in the films, as Lynne Attwood argues(b), I guess we cannot dismiss Olgha’s figure as embodying motherliness of the super-human family: she nurtures and educates young pioneers-children of the State (although to what extent portrayed naturally/schematically is evidently a debatable question). The disposition of Olgha and Veriko on the opposing power-ful/masculine and powerless/feminine poles is also manifested in their life occupations: Olgha, a leader of Young Communist League, is a social activist, public realm’s agent; whereas Veriko earns her life doing laundry - a traditional domestic female labor - is a signifier marking her passive, oppressing and domesti-cating feminine position. In Saba an image of a modern soviet woman embodying full agency and inde-pendence is produced by Olgha’s character. Even if on the symbolic level she personifies the public realm, “mother of the super human family”, nevertheless, it does not give a possibility to assume that fem-ininity has acquired “positive” terms: taking into consideration Olgha’s androgyny, contrasted to suffering feminine Veriko, it becomes evident that regardless the persuasive representation of a strong woman, feminine is still encoded as weak and passive, whereas the strength and agency is defined as masculine.

Situating Saba’s female representations in a wider discourse

In this section I will look at the general representations of the New Soviet Woman and see to what extent they apply to Olgha’s character. The process of turning women into more active agents, the goal that was on party’s agenda even before the revolution (as they represented half of the population and consequent-ly their support for the new order was crucial) was reflected in women’s look as well, that would give a picture of a new woman dressed in more masculine fashion. In Russia it was common to the extent that it was a stereotype. The “metteur en scene” Foregger and dramatist Vladimir Mass, created theater masks for “types,” the leather-jacketed woman, “who spoke only in slogans and militated, in imitation of Kollon-tai, for ‘the theory of free love’,” was one of these models representing “generalized expression of real-life people” (Yutkevich, 1973, pp. 25-26). Although, this type of women was not approved by everyone even among the revolutionaries: as Lynne Attwood observed, Eisenstein was against such a militant female type in general: quoting Novy Lef critic in October Eisenstein, who was an ardent supporter of Bolshevik revolution did not only make a satire of women soldiers defending the Provisional Government, but women in military in general. It is obvious if we compare them to the Bolshevik women in the same film, who are not fighting with arms, but fulfill administrative duties (Attwood, 1993). We can assume that such a “militant” type might have been quite common in Georgia as well, appealing to a letter giving advice to the women delegates how to work with peasant women and also pointing to the dressing style among other things, published in Mshromeli qali in 1924 (that time called Chveni gza [Our way]). The author (cer-tain S. Afaneli) stated that “it is true that there are workers and peasants in our party, but it is not enough to only have a peasant surname. Rather it is necessary to have such a method of approach and appear-ance that a working woman is pleased when she sees you. And if you cut your hair shortly, dress in tu-zhurka [military type leather jacket] and put on a zhoke [a masculine type hat] and moreover, stick a ciga-rette in your mouth, and go to a peasant woman like this, she will not look at you at all, and she will not believe you, even if you talk thousands of pearl words. Working among city women is another matter. These women are more developed, but self-restraint is still necessary, as you will also meet here old-fashioned women” (Afaneli,1924, p.34). Elizabeth A. Wood, as a result of analyzing early twenties Russian journals, argues that “destroying all ‘femininity’ in herself, failing to be an ‘object of pleasure’ for her hus-band” (1997, p. 204) was a common charge made against New Soviet Woman. The New Woman was not quite popular among communist men either: according to Elizabeth A. Wood, the communists as hus-bands were “no better and sometimes were worse than ordinary workers and peasants” - they did not let their wives to attend meetings or be politically active and they did not want a New Soviet Woman as a wife, but were rather going for non party women; quoting one of them as saying that “he really didn’t see a kommunistka as a woman; she was more a comrade at work” (Wood, 1997, p. 205). The situation was very much similar in Georgia. Mshromeli qali’s correspondents were also complaining multiple times that the communists did not encourage their wives’ party activities but rather “pickled them at home” as one of them sarcastically remarked (Khutsishvilisa, 1924). Thus the outlines of a New Woman in 1920s are the following: militant masculine looking activist, vigorously involved in public realm, although this image was not much appealing for communist men themselves. Olgha,- the only representation of the New Soviet Woman provided in Georgian silent films of 1920s,- perfectly fits in the provided descriptions: she is mili-tant like Foregger’ s and Mass’s leather jacketed woman, (or an activist woman as described by Afaneli), she ardently preaches and uses phallic gestures. She is androgenous and we only see her as an ardent activist and comrade.

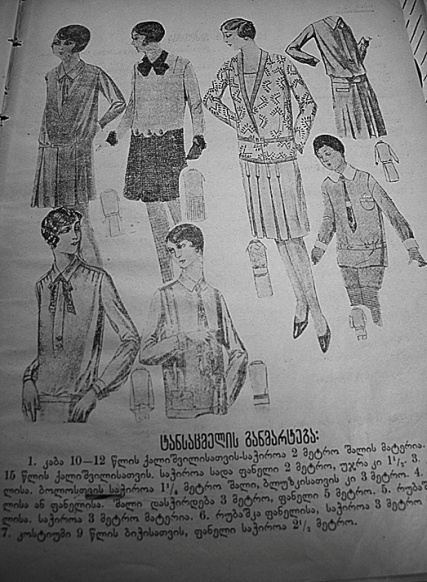

I have already noted above that Mshromeli qali was informing women workers and peasant women about the local and international politics, the party’s activities, simultaneously providing them with educational information of different types: starting from geography and ending with how to take care of various mala-dies, live-stock, etc. It is also very interesting to follow the journal’s line of thought in terms of observing the kind of woman it was promoting: during mid-twenties it was calling and encouraging women to be-come actively engaged in the party work and the building of communist state, to provide the journals with letters from provinces, be actively involved in elections, in women’s circles, etc. However, starting from the late 20s, the journal’s temper changes: the issues become strikingly feminized in terms of offered themes: the politics is still in focus but now the journal gives advices not to women activists but rather to housewives; a new section, displaying models of clothes for women and children is introduced with an accompanying instruction how to sew them (initially it appears in the September-October issue of 1928, Fig. 17), and the journal dedicates a long section to recipes, as well as how to take care of clothes and gardening. According to Elizabeth A. Wood, in the beginning of twenties there was an active debate on the modes of life, which among such essential issues as bribe-taking, drinking, religiosity and anti Semi-tism as reasons of excluding from the party, also included such topics as the line between “freedom” and “decadence” in sexual matters, spouse responsibilities towards each other and their children, and whether young Komsomol men should wear ties, while women rouge and lipstick (Wood, 1997). It is obvious that the issue of the New Woman was a question of debate and Olgha’s type was not unanimously approved. In fact the discourse around New Woman was quite hybrid. In Mshromeli qali there are invocations to be involved in the military service and learn how to shoot, but the photograph of the “best women shooters” predominantly displays not the leather-jacket masculine type women activists, like Olgha, but rather femi-nine, elegantly dressed women (Fig. 18). Even if “equality” of the 1920s assumed that “women should be exactly the same as men” (Turovskaya, 1993, p. 144) by the beginning of thirties it became clear that women had to preserve their femininity, no matter how masculine their job was. Rabotnitsa guaranteed its readers that “female workers on the Motrostroi [acronym for Moscow subway construction project] exchanged their overalls for fashionable dresses at the end of the working day: ‘if you were to meet one of our female metro-builders at the theater or a party, you would not be able to guess that she works under-ground”’ (Attwood & Kelly, 1998, p. 274). The change of mood of Mshromeli qali reveals an existing inter-nal contradiction in the discourse of femininity as advocated by the party and shows signs of drastic changes in the construction of the new woman’s femininity in Stalin’s time to come: according to Lynne Attwood, the 1930s were marked with a new attitude towards dress and appearance, which encouraged women to dress in a more feminine but simultaneously practical style (Grant, 2013).

Fig. 17

Fig. 18

Conclusion

As illustrated, the New Soviet Woman was subject to many controversies. Even if it was unanimously clear on the party agenda that women had to emancipate and take the same position in the soviet state as men, they had to become comrades and women citizens, it was not quite clear what this camaraderie meant. The equality assumed that women should be the same as men, hence they should perform the same traditionally masculine tasks, be the same ardent activists, etc. Besides ideological transformation, it implied changes in look as well. Femininity and agency were incompatible in the New Woman. But this kind of “the same as man” image of women was not greeted even by Bolshevik men, when it came to choosing a partner. They did not find a “comrade” appealing a bit as Elizabeth A. Wood shows (1997). This internal antimony within the discourse caused the modification and manipulation with the official image of the Soviet woman. In order to explore what a Soviet woman’s role model was in the Georgian context in 1920s, I have examined women’s representations in Mikheil Chiaureli’s Saba, which is the only film of the decade offering the images of modern women juxtaposed with the representations/line of women workers journal. In Saba women are no opposed in the frame of class binary system anymore, that was widely characteristic to Georgian films in the beginning and mid-20s. The women in the film: Veri-ko and Olgha are modern women from the working class. It is the camera and their positioning in the frames that define their different social positions: as already noted above Veriko is mostly shown from the high angle shot, which emphasizes her vulnerable position, whereas Olgha, on the contrary, is framed from the low angle shot. Besides the shot angles, Olgha’s powerful position is manifested by the frequent use of phallic gestures while talking. Contrary to Veriko, who is in the need of help, passive and slim, Ol-gha is robust and has a masculine appearance. Olgha is an androgynous agent of the public realm. Be-sides her apparent masculine features and powerful gestures, she also manifests caring-a feature of motherliness (I read it as a motherliness and not as a male protectiveness, considering that she nurtures young pioneers and appears something like a social mother): owing to her intervention the problem is eradicated from the domestic scene. An emancipated image of a New Soviet Woman embodying full agency and independence is produced. Although as the examination of Mshromeli qali (and Russian journals) showed, this image was not unanimously agreed on and the New Soviet Woman was subject to controversies. Nevertheless, Olgha’s character does not give chance to assume that femininity in the film and in the ideological discourse generally has acquired “positive” terms: taking into consideration the androgyny of Olgha, contrasted to suffering feminine Veriko, including their life-earning occupations (Ol-gha’s outdoor, social activity and engagement in an open space and Veriko’s job of doing laundry in her household, a traditional feminine, passive employment) it becomes evident that regardless the persua-sive representation of a strong, active woman, feminine/femininity is still encoded as weak and passive, whereas the strength and agency is defined as masculine.

________________________________

Bibliography:

Afaneli, S. (1924). Mushaoba qalta shoris sofelshi [Working amidst women in villages].

Chveni gza, 10, 33-34.

Amirghanov N. (1928, June 5). Sastsenaro saqme sakartvelos sakkhinmretsvshi [Cinema

script business in Georgian State Cinema Production]. Komunisti, p. 7.

Arendt, H. (1998). The public and private realm. In The Human Condition (M. Canovan,

Trans.), (pp. 28-59). Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press. (Original work

published in 1958)

Attwood, L. & Kelly, C. (1998). Programs for identity: The ‘New Man’ and the ‘New Woman’. In

C. Kelly and D. Shepherd (Eds.), Constructing Russian culture in the age of revolution:

1881-1940 (pp.256-290). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Attwood, L. (1993). Women, cinema and society. In L. Attwood (Ed.), Red women on silver

screen: Soviet women and cinema from the beginning to the end of Communist era

(pp. 19-132). London: Pandora Press.

Bernstein, F.L. (2006). The withering of private life: Walter Benjamin in Moscow. In C. Kaier & E.

Naiman (Eds.), Everyday life in early Soviet Russia, Taking the revolution inside

(pp.217-229). Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Burdzenize, N. (1972). Politmasobrivi mushaoba saqartvelos qalta shoris 1921-1929 [Political and

Massive Work among Georgian Women in 1921-1929]. Tbilisi: Metsniereba.

Chkheidze, N. (2013). An interview enclosed to Saba (DVD), issued in the frame of the conjoined

project of journal Tskheli Shokoladi and Georgian Film.

Grant, S. (2013). The quest for an enlightened female citizen. In Physical culture and sport in

Soviet society: Propaganda, acculturation and transformation in the 1920s and 1930s (pp.

72--98). New York, NY: Routledge, Taylor& Francis Group.

Hochmuth, D. (producer), Bulgakowa O. (director) (2008). Factory of gestures: Body language in

film. [DVD]. Stanford: Stanford Humanities Lab.

Kenez, P. (2001). Cinema and Soviet society: From the revolution to the death of Stalin.

London: I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd.

Khutsishvilisa, M. (1925). Qalta shoris mushaoba Dushetis mzrashi [Work among women in

Dusheti]. Chveni gza, 17-16, 36-37.

Kollontai, A. (1921).Theses on Communist morality in the sphere of marital relation, ( A.

Holt, Trans.). Retrieved from

https://www.marxists.org/archive/kollonta/1921/theses-morality.htm

Makharadze, I. (2014). Diadi munji: Qartuli munji kinos istoria [History of Georgian Silent

Film]. Tbilisi: Bakur Sulakauri Publishing House.

Miller, J. (2010). Soviet cinema, politics and persuasion under Stalin (pp.1-14, 53-56).

London, New York: I.B. TAURIS.

Rimberg, D.J. (1973). The motion picture in the Soviet Union: 1918-1952: A sociological

analysis. New York, NY: Arno Press, A New York Times Company.

Rist, Y. (1925). Proshloe i nastojashee [Past and present]. Sovetskii ekran, 3, 2.

Transchel, K. (2006). Under the influence: Working-class drinking, temperance, and

Cultural Revolution in Russia, 1895-1932. Pittsburgh, PA: University of

Pittsburgh Press.

Trotsky L. (1994). Vodka, the church and the cinema. In R. Taylor &Ian Christie (Ed. &

Trans.), The Film Factory, Russian and Soviet cinema in documents 1896-1939

(pp. 94-97), Abingdon: Rutledge. (Original work published in 1923)

Turovskaya, M. (1993). Women’s cinema in the USSR. In L. Attwood (Ed.) Red women on silver

screen: Soviet women and cinema from the beginning to the end of Communist era

(pp. 133-140). London: Pandora Press.

Wood, E.A. (1997). The baba and the comrade: Gender and politics in revolutionary

Russia (pp.13-48, 194-222). Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Youngblood, D.J. (1992). Cinema as social criticism: The early films of Fridrikh Ermler.

In A. Lawton (Ed.), The red screen, politics, society, art in Soviet cinema (pp.

66-89). London: Routledge.

Yutkevich, S. (1973). Teenage artists of the revolution. In L. Schnitzer, J. Schnitzer and M.

Martin (Eds.) (D. Robinson, Trans.), Cinema in revolution, the heroic era of the Soviet

film (pp. 11-42). New York, NY: Hill and Wang.

[a] Contemporary Georgian critics often remark that the fight against alcoholism was not inherently Georgian and it was more a “Russian” problem (Makharadze, 2014); also it was not vodka, but rather consuming wine that was an authentic and widespread ritual in Georgian citizens’ lives.

[b] In particular on the example of Vsevolod Pudovkin’s Mother, where a peasant woman becomes a political subject through her son and her son’s friends, and Abram Room’s Bed and Sofa (Attwood, 1993) where the female protagonist refuses to make an abortion and leaves her two men to search a new life with her baby instead), and woman’s stressed economical and individual independence was very frequently juxtaposed with maternity (in Fridrikh Ermler’s Katka the Apple-seller for example.