ახალგაზრდა მკვლევართა ჟურნალი № 1 ივლისი 2015

რეზიუმე

ვარდების რევოლუცია დასავლეთის და განსაკუთრებით აშშ-ს მიერ აღქმული იქნა, როგორც დემოკრატიული გარდატეხა და სამოქალაქო საზოგადოების გამარჯვება ყოფილ საბჭოთა კავშირში, რამაც შესაბამისად განაპირობა მათი მხრიდან საქართველოს მიმართ მხარდამჭერი პოლიტიკა ამ უკანასკნელის მკვეთრად განსაზღვრული პროდასავლური კურსის პარალელურად. თუმცა ქართული პოლიტიკა 2003 წლიდან მოყოლებული ნაკლებად თუ დახასიათდება, როგორც თანმიმდევრულად დემოკრატიული. მიუხედავად მნიშვნელოვანი მიღწევებისა, დემოკრატიის კუთხით გადამწყვეტ პროგრესს ადგილი არ ჰქონია და პირიქით, ზოგიერთი დემოკრატიული ფაქტორი გაუარესდა კიდეც. თუმცა ამას ამერიკის მიერ საქართველოსთვის გამოყოფილ დახმარებაზე გავლენა არ მოუხდენია, უფრო მეტიც აშშ-ს ოფიციალურ დისკურსში გამუდმებით გაისმოდა საქართველოს, როგორც დემოკრატიული წარმატების მაგალითად დახასიათება.

ქვემოთ მოცემული კვლევის მიზანია აშშ-სა და საქართველოს შორის 2003-2012 წლებში აღნიშული ურთიერთობის სიღრმისეული

შესწავლა. თემის მიზანია წარმოადგინოს 2003 წლიდან საქართველოში დემოკრატიზაციის და ამერიკის დემოკრატიაზე ორიენტირებული პოლიტიკის ემპირიული კვლევა. კვლევის არგუმენტი მდგომარეობს იმაში, რომ საქართველოს მიმართ აშშ-ს პოლიკიტის განგრძობათობის გაგება შესაძლებელია აშშ-საქართველოს ურთიერთობების ისტორიული პროცესის ჭრილში განხილვით, რომლის მიხედვითაც ამერიკულ დისკურსში მტკიცედ ფესვგადგმული იდეები გადავიდა ე.წ. ინსტიტუციურ დამოკიდებულებაში (path dependency), რასაც ქართულ რიტორიკაში დემოკრატიული მისწრაფებები ამტკიცებდა.

საკვანძო სიტყვები: ფოლკლენდის კონფლიქტი, პოლიტიკური ელიტა, დივერსიული ომი, საზოგადოებრივი აზრი

Abstract

The Rose Revolution was perceived by the West and especially by the U.S. as a democratic breakthrough and a victory of civil society in the former Soviet Union which in turn shaped its highly supportive policy towards Georgia. This policy was consistently reinforced by Georgia’s clearly defined western agenda. But Georgia’s policy can hardly be considered as a steady path towards democracy. Despite some achievements, Georgia did not manage to make decisive progress towards democracy and even performed poorly on some key democracy indices. Nevertheless the U.S. continued to provide ample assistance to the country throughout this period and hailed democratization in Georgia as a success.

This enquiry seeks to explore this peculiar correlation between the U.S. and Georgia in 2003-2012. It aims to offer on the one hand,

a comprehensive empirical examination of the performance of democratization in Georgia and on the other hand, democracy oriented US policy. Consequently it is argued that a reasonable understanding of US policy consistency in Georgia stems from firmly embedded ideas which resulted in path dependence as they were constantly reinforced by democratic aspirations in Georgian rhetoric. The article looks at US-Georgia relations in historical time sequence.

Keywords: Foreign Policy, Historical Institutionalism, US Foreign Policy, Georgia, Democratization

1. Introduction

Since Georgia regained its independence in 1991, it maintained positive relations with the US, but its foreign policy path can hardly be considered consistent. Affected by a multitude of factors in the ambiguous transition process, Georgian foreign policy evolved with reactive features, but the last decade has seen a revision in this trend as a result of dramatic, historical events.

After the Rose Revolution, Georgian foreign policy was defined clearly as pro-Western. In Europe

and even more so in the United States, the revolution was immediately accepted as a harbinger of democratization that defined the country’s distinguished relations with the US. These relations, following the “democratic breakthrough” were mutually reinforced; Georgia set its Western agenda and constantly expressed its aspirations for democracy and pledged reforms, while Washington provided continual democracy assistance. Despite this democratic euphoria, Georgia’s dedication to democracy was incon sistent, and consequently, its democratic image started to fade. Although the country could brag about some achievements such as reducing bureaucracy and corruption, and improving public services and infrastructure, there was not consistent success in terms of democratic progress. Nevertheless , US assistance aimed at Georgia’s democratic consolidation and transition toward a free market economy not only remained ample, but even increased at some points. This peculiar linkage has characterized US - Georgia relations since the Rose Revolution in 2003.

This enquiry attempts to undertake an in-depth study of US-Georgia relations in 2003-2012 and to substantively analyse it in time sequence as a process rather than an ad hoc event in the specific context. More specifically it is an attempt to further explore the consistency of US policy in Georgia, follow its development and a number of its characteristics along with the democratic performance of Georgia since the Rose Revolution. Rather than examining the foreign policies of the US and Georgia as ad h oc events, they will be discussed as an evolving stream of interactions analysed in historical sequence and continuity. The paper argues that these interactions led to path dependency at the policy level, which explains US foreign policy stickiness which is exemplified by the US adhering to its initial plan from 2003 throughout this period.

The first section of the article explores the respective literature on foreign policy decision -making, scrutinizes mainstream theories and discusses the flaws they encompass when referring to this specific case. Correspondingly, a more pertinent theoretical framework of historical institutionalism is pre sented which is capable of overcoming the shortcomings of the other approaches. The next section is devoted to identifying indicators of democratic reform and empirically examining the consistency of democratic progress in Georgia. The primary section of the paper is devoted to examining US foreign policy on two levels: financial assistance for democratization in Georgia and official rhetoric related to democratization. These are discussed together with Georgian democratic performance between 2004 and

2012. The last section attempts to develop a reasonable explanation of different characteristics of US policy including consistency, for which I base the analysis on historical institutionalism arguing that the Georgia-US relationship should be assessed in the historical context as a long-term process, with continuity in both official Georgian and American discourses. In conclusion, it is argued that along with inconsistent democratic performance by the Georgian state, US policy has maintained consistency by embracing democratization as a long-term goal, which was eased by the rhetorical democratic aspirations of Georgia. This development is better understood by the notion of path dependency, and hence constrained by past trajectories.

2. Alternative Explanations of US Foreign Policy Behaviour

Foreign policy analysis is generally dominated by mainstream, rationalist approaches. Both realism and liberalism portray states as selfinterested, rational actors striving to achieve their interests. While realists characterize states as power maximisers, liberals see them as constantly aiming at enhancing economic prosperity (Kurki and Wight, 2007, p.20).

A realist explanation of US interests and involvement in Georgia has a geopolitical character related to dominating in the region, balancing Russia and reducing its influence (Macfarlane, 1999, p.19). Influence in the region can provide the US with a transit route and new resources. Georgia’s geographic location can explain its importance for the US, with it perceiving the country as a security partner or an “energy corridor” (which has an economic as well as security purpose) to Central Asia and the region’s resources (Mitchell and Cooley, 2010, p.21).

However, this argument has some shortcomings. There are dozens of countries that border Oil producing states located near the Middle East, but they receive less attention from the US (Mit chell, 2006, p.670). Furthermore, security issues are hardly the focus of US relations with Georgia. In terms of security, US-Georgia relations were defined by the Charter on Strategic Partnership signed in January 2009 in Tbilisi. Similar charters have been signed by the US with Afghanistan, Australia, Brazil, India, Indonesia, Israel, Pakistan, and Ukraine (Mitchell and Cooley, 2010, p.17). After closely examining the Charter and its outcomes, it can hardly be evaluated as the basis of a security agreemen t. Its main emhasis falls on underscoring democratic achievements and setting further goals, rather than providing any security guarantees. For instance, similar charters with the Baltic states in 1998 included a chapter on integration with NATO, the EU and OSCE which is absent in the Georgian case and replaced by a chapter on democracy (Mitchell and Cooley, 2010, p.19).

From the liberal perspective, some claim that opening markets for US goods and services di rectly serves US economic interests. Others emphasize the importance of Georgia’s location to serve as an energy corridor. But, as evidence shows, US investment in the region is highest in Azerbaijan for which it provides the least assistance in the region (Nichol, 2013, p.48). Thus relating economic interests with democracy assistance hardly makes sense.

Another explanation rests upon the ideological unity between the states with Georgia’s western identity (Kakachia, 2012, p.4) and the US ideological perception of Georgia’s importance based on its democratic credentials (Mitchell and Cooley, 2010, p.14, p.18). Although this approach overcomes the downfall of others by emphasizing the socialization process, it also fails to explain the immense change in

2003.

Although these theoretical approaches present a reasonable understanding of US-Georgia relations, they still hold some shortcomings that lead to only a partial explanation. More specifically these approaches take specific foreign policy decisions as ad hoc events (Kuperman and Ozkececi, 2006, p.538). This tendency is further characterized by fixed preferences for actors as defined by the rationalist theories and misses the point that foreign policy decision-making is an ongoing process rather than a one-time act and later behaviour is a subsequent element of the previous.

Claiming that states have fixed preferences, rationalist approaches miss the element of sociali zation and discussion of foreign policy decision making in context. Although constructivism captures the element of socialization whilst emphasizing ideas and shared norms and reasonably explains the continuity of policy, it is not very helpful for understanding change, which has to come as an exogenous shock (Thelen, 1999, p.387). Identities and ideas evolve over time, but the particular relations between the US and Georgia had its founding moment which is best explained by a historical institutionalist framework.

3. Theoretical Framework and Methodology

For mainstream international relations theories, history is used only in case stu dies and for empirical evidence. Historical institutionalism, which is not a theory but more a theoretical tradition, fills this gap by moving “toward theorizing conditions under which temporal processes matter”. It is not only that history matters, but the question of how and when it matters in terms of influence on political behaviour (Fioretos, 2011, p.369). The basic assumption of historical institutionalism is that timing and sequence of events shape political developments and earlier events shape later ones (ibid p.371).

Historical institutionalism is a tradition, which is part of comparative politics and is a blend of two intellectual developments: political sociology and the approach that ascribes significance to institutions (Peters, 2005, p.1279). Despite the attention it pays to institutions, historical institutionalism is distin guished from sociological and rational choice institutionalism mainly by its analysis of preferences. Rational choice institutionalists “start with individuals and ask where institutions came from, whereas historical institutionalists start with institutions and ask how they affect individuals’ behavior” (Thelen, 1999, p.379). Whereas rational choice theorists emphasize endpoint comparisons, historical institutionalists’ preferences are guided by “point-to-point comparisons”. Individuals generally evaluate alternatives by assessing costs and benefits to new circumstances. Thus they always consider the costs of losing their investments in the past. Shaping preferences depends on the degree of change in history. So, change takes place when the benefits of adaption outweigh the costs of change (Fioteros, 2011, p.373). Hence, historical institutionalism pays attention to the sunk costs. Therefore, investments in the past and the perception of the costs of their change are central to historical institutionalism (p. 376).

Historical institutionalism does not break history down into pieces for evidence or cases. It focuses on the time sequence and long-term processes instead, and thus is very useful in explaining the continuous policy of the US towards Georgia or consistent democracy aid in the context of inconsistent democratic development in the country. Historical institutionalism claims that the policymaking system is conservative and aims to preserve existing patterns. Institutions are resistant to change via selfreinforcing processes. An extended time period of stability is referred to as “path dependency” and is changed only by “formative moments” or socalled “critical junctures” (Pierson, 2000, p.252). So, path dependence explains the stickiness characterizing many political developments, and the change is related to a critical juncture or a breakthrough in history. Consistency in US foreign policy towards Georgia and its star t at the beginning of the Rose Revolution is discussed here. Consequently, the theory is considered useful for the Georgian case.

The primary focus of this article is the study of the correlation between Georgia’s democratiza tion process and respective US policy targeted at democracy promotion. Both quantitative as well as qualitative data is analysed for this purpose. To evaluate Georgia’s democracy performance, two Free dom House reports are used: Freedom in the World and Nations in Transit. US policy is evaluated on two levels: first, assistance is assessed based on US financial aid to Georgia directly stemming from the state budget expressed in U.S. Government (USG) programs and Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) funds. Second, it is examined on the rhetorical level. The path dependency argument, besides consistent financial support, is also shown by content analysis of Georgian and American discourses. Twenty two official U.S. statements and speeches on Georgia in 2009-2012 were analysed. In order to go beyond only diplomatic statements, domestic discussions and speeches are also examined. These include the discussions of the US Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, and statements made by Georgia W. Bush, the US Secretary of Defence and the US Secretary of State. To analyse Georgian rhetoric, Georgian officials’ speeches and statements at meetings with US representatives and official state documents such as the Foreign Policy Strategy and National Security Concept are examined.

4. Georgia’s Western Agenda

The Rose Revolution in 2003 was appraised as a democratic breakthrough for Georgia and already in 2005 Georgia was labelled as “a beacon of liberty” in the region by George W. Bush. In the West, the revolution was taken as a harbinger of a thriving democratization process not only because Shevardnadze’s corrupt regime was peacefully overthrown, but also because the new government pledged to turn Georgia into a Western and democratic country (Mitchell, 2010, p.34). Generally there is a lack of clarity in the definition of the West, and what it really refers to, which makes it hard to define a western agenda. However, there are some consistent ideas related to the concept that stem from liberal values (Macfarlane, 1999, p.3), which could be broadly grouped as democratization.

The term democratization refers to both “transition” and “consolidation”. Therefore it includes both regime change – from authoritarian to democratic – and adjusting behaviours to democratic structures and norms (Pridham and Vanhanen, 1994, p.2). Democracy criteria identified by various scholars can provide a comprehensive set of factors that can be used to evaluate the democratization process. The basis of democracy or the minimal criteria lies in electoral procedures – how free and fair elections are, if the opposition has a chance of winning and most importantly if it is more than just a fa çade democracy (Schmitter and Karl, 1991; Cheibub et al., 1996; Fish, 2002) . It is essential to evaluate the performance of the government after elections as relates to accountability, concentration of power, checks and balances, independence of judiciary, the situation in terms of party polarization and the role of the opposition, the level of corruption, civil society, media independence, political rights and civil liberties (Carothers, 2002; Jones, 2012; Przeworski, 2000; Jawad, 2005; Diskin, 2005). Correspondingly this enquiry will address the above listed factors for a comprehensive analysis of the democratic condition in Georgia. Two reports that incorporate most of the criteria above are written by Freedom House: Freedom in the World and Nations in Transit.

5. Democratization performance

Two Freedom House reports provide an analysis of a pertinent blend of factors related to both individual rights as well as government performance, which are useful for evaluating democratization processes.

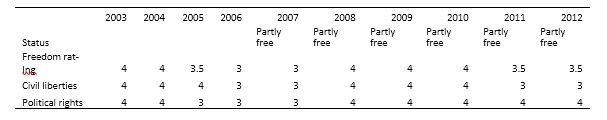

Table 1. Freedom in the World- Georgia. Source: Freedom House

The Freedom in the World report mainly refers to the individual rights expressed in civil liberties and political rights. Georgia remained ‘Partly Free’ in 2003-2012, but the overall freedom rating fluctuated. The score improved in 2005-2007 and declined between 2008 and 2010. In 2011, it improved slightly (by 0.5 points). Similar changes took place in civil rights, but the political rights ranking remained static since 2003, with the exception of the years between 2005 and 2007. Overall, although the civil liberties score looks more impressive in 2012 compared to 2003 (without a constant positive trend though), political rights remained unchanged.

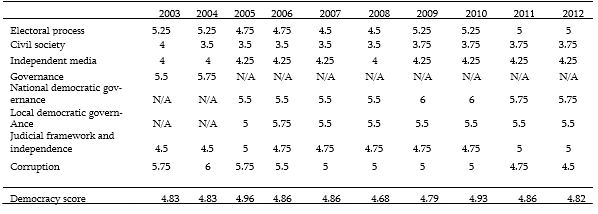

Table 2 . Nations in Transit Ratings and Averaged Scores. Source: Freedom House

As for the Nations in Transit criteria, there were some improvements in electoral process, civil society, local democratic government and corruption, but scores worsened for independent media, national democratic government, judicial framework and independence. When all the factors are considered, compared to 2003 there were practically no changes in the overall democracy score by 2012 (from 4.83 to 4.82). With this score, Georgia belongs to electoral democracies with minimal standards for the selection of national leaders. At this level “democratic institutions are fragile and substantial challenges to the protection of political rights and civil liberties exist. The potential for sustainable, liberal democracy is unclear” (Freedom in the World, methodology).

Now we can go to each indicator in detail and assess the overall democratization of Georgia using both reports and scholarly works.

In 2012, Freedom House did not consider Georgia an electoral democracy, because of the number of abuses in 2008 presidential and parliamentary elections and 2010 local elections as reported in OSCE reports. In the 2010 elections, there was progress in terms of meeting international election standards, but still some misconduct was mentioned (Freedom in the World 2012 report).

The main concern about Georgia since 2003 was the concentration of power in the executive branch. As Jones notes, Georgia has, “retreated from ’feckless pluralism’ and was getting closer to ’dominant power politics‘ in which state merges with the ruling party” (2012, p.118). As Fairbanks (2004) reports, Georgia’s

leader had turned the country from a superpresidential into a hyperpresidential one. Constitutional reform in 2004 weakened the role of the parliament and “allowed for a rule by presidential d ecree,” that removed checks and balances in the political system (Cornell and Nilsson, 2009, p.253). As a result of the reform, the president had the right to appoint the Prime Minister and the cabinet, mayors and other low-ranking officials. He could also dissolve parliament if it rejected the budget twice (Mitchell, 2006, p.672). If before, the president had the right to appoint only three of nine constitutional Court judges, now the president had the right to name all of them (Kalandadze and Orenstein, 2 009, p.1410). Before the revolution, about 99% of profit taxes were under the supervision of local budgets, but after the revolution 100% of revenue was left for the central budget that allocated it to local ones. These changes made local governments dependent on the central government (Papava, 2006, p.663, Nations in Transit 2012).

The United National Movement was the dominant party from 2004 until 2012 and the opposition, although filled with some exallies of Saakashvili, did not manage to form a considerable force (Freedom in the World 2012). Parties in Georgia remained “weak, unstable and focused on individuals rather than on political ideas and programs” (Jawad, 2005, p.20).

Although the legal framework for Georgian media met international standards, the main concern was the lack of transparency of ownership and the pro-governmental bias in some of the leading channels (Freedom House). As Freedom House reported, the judiciary suffered from “significant corruption and pressure from the executive branch” (Freedom in the World). Some changes were introduced such as pay increase for judges and jury trials, but some major concerns still remained. The court was considered relatively independent in civil law, but many of the criminal cases were influenced by t he Prosecutor’s Office (Nations in Transit).

After the Rose Revolution, there was a mass migration from the NGO sector to the public service, which resulted in the weakening of the former. NGOs no longer played a watchdog role (Mitchell, 2006, p.673), and their influence on the government was weak (Nations in Transit). Although their registration process was easy, they could operate without restrictions and their number was considerably high. The unwillingness of the administration to consider their positions limited their influence (Freedom in the

World).

To merge the results in both economic and political developments, the Georgian government has demonstrated some impressive developments in macro economy such as the struggle against corruption as well as in electoral processes. Nevertheless, these positive changes were accompanied by some considerable downfalls. Economic growth did not bring improvements in unemployment, poverty and inequality. Some indicators of democracy such as media freedom, judicial independence, and systems of checks and balances in fact declined. Reforms after the Rose Revolution mainly envisaged state-building activities, and this focus on the modernization process was not necessarily compatible with de mocracy building in the Georgian case (Cornell and Nilsson, 2009, p.254).

6. US Financial Assistance to Georgia

Although most of the reforms were not necessarily consistent with the Western agenda or

democratization and economic reform, but rather with state-building (Mitchell, 2009), western assistance remained ample after the revolution. Besides the U.S., western actors included the EU (and its financial institute the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development) and NATO that are without a doubt western due to their composition. International financial institutions such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank are often considered as western as western states maintain the majority of the

power in these organizations, and they reflect western models of market economy (Macfarlane, 1999, pp.6-7). Their assista

nce to Georgia was considerable.

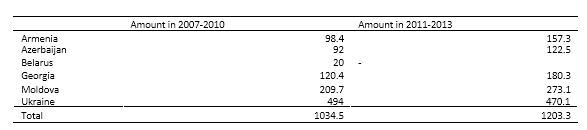

For instance, after Ukraine and Moldova, Georgia was the largest recipient of EU funding with

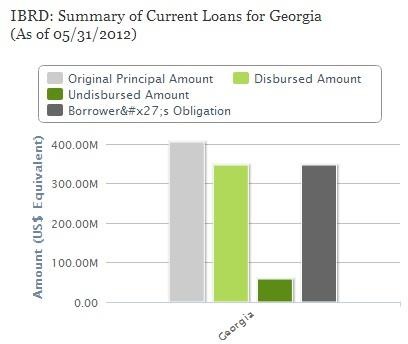

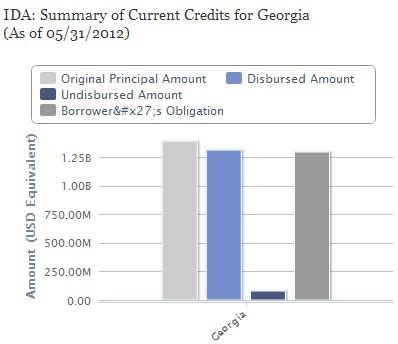

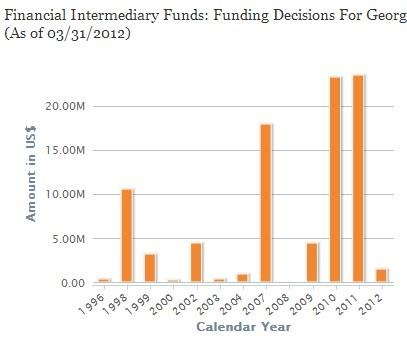

€300 million overall in 2007-2013. In 2007-2010 Georgia received €120 million and €180 million in 2011-2013 (Table 3). The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) supports Georgia’s transition towards market economy. By March 2012, the institute had 146 investment projects in the country equalling €1.6 billion. By 2012, Georgia’s loans from the World Bank totalled approximately $408 million, while credits totalled $1,300 million, and funding equalled $1.5 million (Tables 4, 5, 6).

Although, the aforementioned actors provided very generous aid packages for Georgia, the United States proved to be an exceptional donor for Georgia starting in 2003. The US is the largest donor to Georgia, and the country received some of the most aid from the United States, per capita, in the world (Nichol, 2012, p.16). The fact that US assistance came in the form of grants, not loans like other

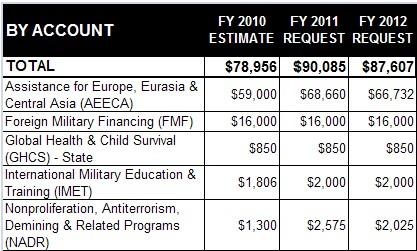

organizations gives it a different significance for Georgia (Mitchell and Cooley, 2010, p.47). After 2004, US assistance for Georgia not only increased, but the country became eligible for special funds from the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC, Mitchell and Cooley, 2010, p.43). Moreover, and what is most interesting, is that the trend did not change much despite negative changes in democratic performance, in a context where the main US goal was focused on democratization: “the consolidation of Georgia’s democracy, its eventual integration into Euro-Atlantic institutions, progress toward a peacefully unified nation, secure in its borders and further development of its free market economy” (US Departm ent of State, 2013, p.419).

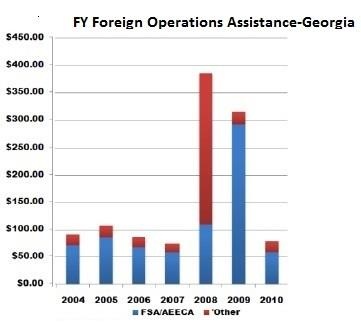

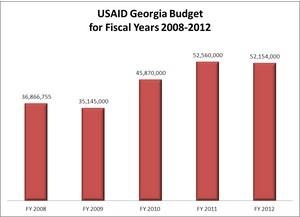

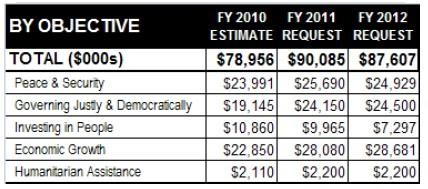

US assistance was received through United States Government (USG) programs such as the Freedom Support Act (FSA) and other programs that covered areas such as peace and security, governing justly and democratically, investing in people, economic growth and humanitarian assistance. The programs aimed “to promote consolidation and advancement of the democratic reforms and to assist Georgia’s integration into the Euro-Atlantic community through the implementation of freemarket reforms” (U.S. Department of State, 2011).

As demonstrated from the tables (7-10), FSA and others programs provided a considerable amount of assistance to Georgia. In 2004, in addition to the former funds, congress introduced a major new global assistance program, the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC). Georgia was deemed eligible for assistance as a democratizing country even though it did not meet the criteria on anti- corruption efforts (Nichol, 2013, p.40). Georgia appeared in a program for countries t hat were considered by Washington to be especially deserving of US aid (Mitchell and Cooley, 2010, p.43). Georgia received $395 million through the program in 2006-2011, and in 2012, it was announced that Georgia was eligible

for the next round of the program as well (Nichol, 2012, p.16). In addition to FSA and MCC funds, in September 2008, after the August War, Secretary Rice announced a multi -year, USD 1 billion aid package for Georgia, to help the country repair the damage after war (Nichol, 2013, p.28). One significant change was the altered direction of US aid. If before 2004, the major recipient of aid was civil society, after the revolution it was received by the Georgian government (Mitchell and Cooley, 2010, p.14).

7. US-Georgia Relations in a Historical Institutionalist Framework

The critical juncture or original moment that shaped subsequent US-Georgia relations was the Rose Revolution. The event was a “turning point” in US-Georgia relations and viewed as the source for their “enduring alliance” (Mitchell and Cooley, 2010, p.14). The revolution was taken as a democratic breakthrough for Georgia. These developments coincided with an increasing emphasis on freedom and democracy on the part of the Bush administration. President Bush’s second inaugura l address marked

the promotion of democracy in the wider Middle East as an important element of official US foreign policy (Cornell and Nicolsson, 2009, p.8).

After 2004, US assistance not only increased but changed direction and instead of aiding civil society in Georgia, funding went directly to the government (Mitchell and Cooley, 2010, p.14). This pattern was maintained, and played the role of self-reinforcement in the process of path dependence. Once Georgia was defined as a “beacon of democracy” and a harbinger of the democratization process in the region, this attitude was maintained as it was demonstrated in US officials’ speeches. This attitude was compatible with the US policy of spreading democracy in the world.

The Rose Revolution was immediately recognized in the West as a significant democratic success. It was perceived as a “triumph of civil society, a victory of freedom and democracy and the grand finale of the ‘third wave’ democratization” (Lutsevych, 2013, p.2). Since then, the US constantl y hailed democratization in Georgia as part of Bush’s foreign policy agenda with the goal of promoting democ racy (Mitchell, 2006, p.670, p.674). But despite Georgia’s significant shortcomings in the consolidation process, the US not only continued its support but promoted Georgia as a democratic success (Mitchell and Cooley, 2010, p.30). For instance, during his visit to Georgia in 2005, Bush only made favorable comments (Mitchell, p.676). In 2007 after the violent crackdown on protests, the US refused to c riticize Georgia publicly and pushed for its NATO membership (Cooley and Mitchell, 2009, p.30).

The attitudes and positions of US officials are demonstrated in their visits and meetings with Georgian politicians, during which US officials consistently underlined the democratic achievements by Georgia and promised further support. In the 22 official statements and speeches by US officials during meetings with Georgian officials in 2009-2012 (obtained from the US Embassy archive in Tbilisi), one noticeable trend from US officials’ speeches about Georgia is their constant emphasis on the democratic achievement of the country. Although most also mention the need for further developments and some of them even underline specific areas to be improved, their expression of unanimous support from the US based on Georgia’s role played in democracy in the world is obvious. No conditionality is even hinted at. In fact, since 2007, democracy indicators for Georgia had worsened. However, this had no significant effect on the US representatives’ attitude, at least officially.

However, it is also true that diplomatic rhetoric might be rather flattering to a certain extent and not able to precisely depict official policy. For this reason, I also looked at George W. Bush’s and Senior Department of State and Defense officials’ statements and Senate committee meetings with a primary focus on depicting criticism of Georgia during the Bush administration. The President and Secretary of Defense mentioned no criticism whatsoever in their speeches, nor did statements maintained in the official archive. As for the rest, the following trend prevailed: recognition of some shortcomings in Georgian democracy related to freedom of the press (Condoleezza Rice, 2008; Matthew Bryza, 2008) and the judiciary, the lack of a strong opposition (Daniel Fried, Assistant Secretary, 2007), and the general condition of democratic institutions (William Burns, Undersecretary of State, 2008). At the same time, this recognition was followed by justification of some deficiencies. For example, the 2007 excessive use of force by the government against protestors was found to be “familiar juvenile delinquencies of young democracies finding their way in the post-Soviet world” (Bruce Jackson, President of the Project on Transitional Democracies, 2008). Achievements outweighed deficiencies; for example, the free elections after the November 2007 clashes were more important (Philip Gordon, Senior Fellow for US foreign policy,

2008). The spirit that followed the rhetoric set democratization as a long-term goal for the provided support (William Burns). It also hailed the general success in development (Daniel Fried, Matthew Bryza) and set expectations for the future that Georgia was on the path towards democracy with the potential to succeed.

Thus stickiness to the initial policy along with inconsistent performance by the Georgian state in democratization was accompanied by some rationalizing and justification. “Juvenile” deficiencies were explained by a complicated context more specifically, by a turbulent phase for the country. At the same time, democratization was set as a longterm goal and success in statebuilding was underlined instead. But the policy primarily embraced the ideas and expectations for Georgia to aspire for democracy, which was the main basis for the US policy in the country. This expectation was strongly reinforced by Georgian rhetoric.

In fact, what stayed unchanged since the Rose Revolution was the rhetoric of Georgian officials.

Both in official texts and speeches, they proclaimed Georgia’s dedication to democracy and emphasis on the notion that Georgia and the US shared common values (Cooley and Mitchell, 2009, p.29). The Georgian government, realizing that western support depended on their aspirati ons for democracy, declared democratization as the main priority of state policy (Cornell and Nilsson, 2009, p.260). Rhetoric strengthened after 2007 when democracy indicators for Georgia started deteriorating. Since 2007, Saakashvili twice “pledged to redouble his efforts to bring democracy to Georgia” (Mitchell and Cooley, 2010, p.36), and even called for the second Rose Revolution in his United Nations General Assembly address, and the “reforms promised were exhaustive” (Cornell and Nilsson, 2009, p.260).

This idea is supported by the official rhetoric analysed for this inquiry including official texts issued in 2003-2012 such as the Foreign Policy Strategy and National Security Concept and speeches by Georian representatives (the President, Prime Minister, Minister of Foreign Affairs) at meetings with US officials. In the documents, Georgia’s belonging to the European family is constantly underlined in terms of shared values (FP Strategy of Georgia, p.21). Aspirations for democracy related values, such as human rights, civil society, civil liberties, and political and religious freedom are underscored (National security concept). Relations with the US are heavily underlined and as stated they are based on the common values that the two countries share (FP Strategy of Georgia, p.22).

This official policy is heard through officials’ speeches as well. While meeting with US represent actives, Georgian politicians constantly emphasized the importance of US support and underlined the country’s achievements as a result of this support. It was frequently mentioned that Georgia became a role model in the region, “a shining example” (Saakashvili, 2010, 2011, 2012). Successful reforms were underscored, and the readiness to go on with reforms expressed (Gilauri, 2010). Strong relations with the US were justified by common values and the need for continuity and deepening of ties frequently mentioned (Saakashvili, 2010; Vashadze, 2009).

8. Conclusion

This research was undertaken to provide a comprehensive understanding of US -Georgia relations, and specifically US democracy-targeted policy in Georgia in linkage with the latter’s performance in democratization. This article refers to the fact that the US policy remained relatively consistent even though democratization in Georgia did not keep up with the pledged reforms and some important indicators even declined. From a historical institutionalist perspective, it argues that the Rose Revolution played a critical juncture role shaping specific policy between the US and Georgia which these two states maintained because of the well-institutionalized ideas created about each other and US stickiness to the past investment in Georgia all reinforced by the positive feedback mainly expressed in rhetoric.

The first part of the enquiry provided empirical research on Georgia’s performance on democracy indicators. While some improvements have taken place in civil liberties, the condition of political rights by 2012 did not change compared to 2003. Some positive changes took place related to electoral processes, civil society and corruption, but a negative trend was observed in the areas of independent media, judicial framework and independence, and national democratic governance. When Freedom House evaluated the transition process in Georgia, the overall score in 2012 was basically the same as in 2003.

Consequently, US policy was studied based on financial contributions as well as US rhetoric. The financial part was accounted for by United States Government aid and the Millennium Challenge Account, both directly stemming from the budget. As the data demonstrated, US assistance not only remained ample throughout the period considered in this article, but even increased e specially after 2008 when in fact democracy scores for Georgia started decreasing. Since 2003 the US also directed a majority of its aid to Georgia directly to the Georgian government. The US officials’ rhetoric was consistent with the financial assistance while constantly promoting Georgia as a democratic success.

The final section of the paper argued that this persistent US policy toward Georgia is better explained by its interpretation in time sequence. Constant reinforcement of this long-term policy was explained by the tendency of path dependency. After the Rose Revolution which was a turning point in US - Georgia relations, the idea of Georgia as a country striving for democracy became well institutionalized both formally and in the attitudes of US officials. For adjusting their behaviour to the framework, confirming information was underlined and negative information filtered out. In the process of adaption, the US set democratization as a long-term goal fed by expectations for Georgia’s future advancement on the path towards democracy. Routines embodied in this relationship had a huge impact on US incentives or options selected for Georgia. Once the US started down this track, considered Georgia a country striving for democracy, adjusted its policy to that attitude, and “invested” in Georgia’s democracy, it was hard to change direction. But the major reason for reinforcement of the policy was the positive feedback from the Georgian side as expressed in some achievements, but mainly in the rhetoric constan tly underlining Georgia’s dedication to democracy and pledging new reforms, which continuously reconfirmed the US’s expectations on Georgia’s aspirations.

__________________________________________

Bibliography

Bryza, M. (2008). Foreign Press Center Briefing. 19 August, 2008. Available from: http://pristina.usembassy.gov/uploads/images/3gFftRYWjoY5v0FDKzc2sQ/Bryza_brief_FPC_082508.pdf

Burns, W. (2008). Senate Committee on Foreign Relations hearing. 17 September, 2008. Available from: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/browse/committee.action?chamber=senate&committee=foreignrela - tions&collection=CHRG&minus=CHRG

Carothers, T. (2002). The end of transition paradigm. Journal of Democracy, 13(1), pp.5-21.

Cheibub, J.A., Przeworski, A., Limongi Neto, F.P. and Alvarez, M.M. (1996). What makes democracies endure? Journal of Democracy, 7(1), pp.39-55.

Cooley, A. and Mithell, L.A. (2009). No way to treat out friends: recasting recent U.S.-Georgian relations.

The Washington Quarterly, 32(1), pp.27-41.

Rice, C. (2008). Interview with Davit Kikalishvili on Rustavi 2. 10 June, 2008. Available from: http://2001-2009.state.gov/p/eur/ci/gg/c7143.htm

Cornell, S.E. and Nilsson, N. (2009). Georgian politics since the August war. Demokratizatsya, 17(3), pp.251-268.

Country Development Cooperation Strategy 2013-2017. USAID, Caucasus Program and Project Support Office, July 2012.

Diskin, A., Diskin, H. and Hazan, R.Y. (2005). Why democracies collapse: the reasons for democratic failure and success. International Political Science Review, 26(3), pp.291-209.

Eastern Partnership Community, 2013. Country allocations. [online] Available at: http://www.easternpartnership.org/programmes/country-allocations [Accessed 5 January 2013].

European Bank of Reconstruction and Development. Fact sheet: Georgia. [online] Available at:

http://www.ebrd.com/pages/country/georgia.shtml [Accessed 7 January 2013].

Fairbanks, C.H. (2004). Georgia’s Rose Revolution. Journal of Democracy, 15(2), pp110-24.

Fioretos, O. (2011). Historical institutionalism in international relations. International Organization, 65(2), pp.367-399.

Fish, S. (2002). Islam and authoritarianism. World Politics, 55, pp.4-37.

Foreign Policy Strategy 2006-2009, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Georgia. Available at:

http://mfa.gov.ge/index.php?sec_id=8&lang_id=ENG.

Freedom House. (2012). Freedom in the World report. [online] Available at: http://www.free-domhouse.org/report/freedom-world/freedom-world-2012 [Accessed 15 December, 2012].

Freedom House. (2012). Nations in Transit report. [online] Available at: http://www.free-

domhouse.org/report/nations-transit/nations-transit-2012 [Accessed 15 December, 2012].

Fried, D. (2007). Remarks at conference – Developing Europe’s East. 1 November, 2007. Available from:http://2001-2009.state.gov/p/eur/rls/rm/c20483.htm

Gordon, P. (2008). Senate Committee on Foreign Relations hearing. 11 March, 2008. Available from: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/browse/committee.action?chamber=senate&committee=foreignrela - tions&collection=CHRG&minus=CHRG

Jackson, B. (2008). Senate Committee on Foreign Relations hearing. 11 March, 2008. Available from: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/browse/committee.action?chamber=senate&committee=foreignrela - tions&collection=CHRG&minus=CHRG

Jawad, P. (2005). Democratic consolidation in Georgia after the “Rose Revolution”? Peace Research Institute Frankfurt (PRIF) reports #73.

Jones, S. (2012). Georgia: a political history since independence. New York: I.B. Tauris & Co.

Kakachia, K. (2012). Georgia’s identity-driven foreign policy and the struggle for its European destiny. In

Caucasus Analytical Digest, 37, pp.4-8. Kalandadze, K. and Orenstein, M.A. (2009). Electoral protests and democratization beyond the color revolutions. Comparative Political Studies, 42, pp.1403-1425.

Kurki, M. and Wight, C. (2007). International Relations and Social Science. In: Dunne, T, Kurki, M. and Smith, S. (eds). (2007). International Relations theories: discipline and diversity. New York: Oxford Uni- versity Press.

Lutsevych, O. (2013). How to finish a revolution: civil society and democracy in Georgia, Moldova and

Ukraine. Chatham House briefing paper.

Macfarlane, N. (1999). Western engagement in the Caucasus and Central Asia. Russia and Eurasia Programme (The Royal Institute of International Affairs). University of Michigan.

Macfarlane, N., Mitchell, L. and Mullen, M. (2011). Foreign assistance: to what degree has Western aid helped Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia? Carnegie Endowment: Washington D.C. [online] Available at: http://www.carnegieendowment.org/2011/11/29/foreign-assistance-to-what-degree-has-western-aid- helped-armenia-azerbaijan-and-georgia/854q [Accessed 26 December, 2012]. Ministry of Economy and Sustainable Development of Georgia. (2012). Georgian economic outlook. Tbilisi.

Mitchell, L.A. (2006). Democracy in Georgia since the Rose Revolution. East European Democratization, 50(4), pp.669-676.

Mitchell, L.A. (2009). Comprising democracy: state-building in Saakashvili’s Georgia. Central Asian Survey, 28(2), pp.171-183.

Mitchel, L. and Cooley, A. (2010). After the august war: a new strategy for U.S. engagement with Georgia. The Harriman Review, 17(3-4), pp.5-69. National Security Concept of Georgia. (2011). Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Georgia. Available at: http://www.mfa.gov.ge/index.php?lang_id=ENG&sec_id=12

Nichol, J. (13 July 2012). Georgia [republic]: recent developments and U.S. interests. CRS Report for Congress. Papava, V. (2006). The political economy of Georgia’s Rose Revolution. East European Democratization, 50(4), pp.657-667. Peters, B.G., Pierre, J. and King, D.S. (2005). The politics of path dependency: political conflict in Historical Institutionalism. The Journal of Politics, 67(4), pp.1275-1300.

Pierson, P. (2000). Increasing returns, path dependence, and the study of politics. The American Political Science Review, 94(2), pp.251-267.

Pridham, G. and Vanhanen, T. (1994). Democratization in Eastern Europe: domestic and international perspectives. London: Routledge.

Przeworski, A., Alvarez, M.E., Cheibub, J.A. and Limongi, F. (2000). Democracy and developmentL political institutions and well-being in the world, 1950-1990. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Saa¬kashvili, M. Speech at the Brookings Institution. From popular revolutions to effective reforms: the Georgian experience. (17 March 2011). Washington, D.C.

Schmitter, P.C and Karl, T.L. (1991). What democracy is and is not. Journal of Democra cy, 2(3), pp.75-88.

Thelen, K. (1999). Historical institutionalism in comparative politics. Annual Review of Political Science,2, pp.369-404. The World Bank. Country summary: Georgia. [online] Available at: https://finances.worldbank.org/facet/countries/Georgia [Accessed 27 December 2012]. The World Bank. (2012). Georgia: public expenditure review. Managing expenditure pressures for sustainability and growth. The World Bank: Washington, D.C.U.S. Department of State. (2011). Foreign Operations Assistance fact sheet: Georgia, annual report 2011. [online] Available at: http://www.state.gov/p/eur/rls/fs/167303.htm [Accessed 27 December 2012]. U.S. Department of State. (2013). Congressional budget justification: foreign operations, annual report 2013. Washington, D.C.U.S. Embassy of Georgia. US officials’ speeches, interviews, statements 2009-2012. [online] Available at:http://georgia.usembassy.gov/latest-news.html [Accessed 10 January].

Appendices:

Table 3. EU funding through European Neighbourhood Policy 2007-2013 (million euros). Source: Eastern Partnership Community

Table 4 . IBRD: Summary of current loans for Georgia in 2012.

Table 5 World Bank credits for Georgia in 2012.

Table 6. World Bank funds for Georgia in 1996-2012.

Table 7. Source: US Department of State

Table 8 Source: US Department of State

Table 9 Source: US Department of State

Table 10 Source: US Department of State