ახალგაზრდა მკვლევართა ჟურნალი № 4 დეკემბერი 2016

Abstract

This paper documents increase in the Quality of Life (QoL) of children reintegrated into their biological families, compared with children living in the large-scale state residential institutions in Georgia. The findings echo outcomes of the studies conducted in developed countries, demonstrating preference and benefits of growing in a family environment. The study applies participatory approach and evaluates outcomes of deinstitutionalization process using children’s conscious judgment of their QoL and their own criteria. Similar assessment is conducted in the countries of the Europe and Central Asia region for the first time.

Three samples of 224 children were representative of all children of the age 11-18 years a) residing in two large-scale state institutions still remaining in Georgia in 2012, b) reintegrated into their biological families, with the state and donor support, c) reintegrated into their biological families only with the state support. The children were interviewed in person using QoL scale, designed for this study based on the original Personal Life Quality Protocol. The study adhered to the principle of voluntary participation and informed consent.

Children perceived themselves to be happier at home and had higher QoL scores. At baseline, QoL score in the institutions was 80%, while after the return home it had increased to 88%. QoL scores did not differ significantly the between groups reintegrated using different methodologies, however demonstrated negative correlation with the length of stay in a family.

The study confirms the positive impact and a preference of a family environment. Though, it calls for a long-term assessment of QoL of reintegrated children, as well as residing in different forms of child care available in Georgia, in order to monitor long-term results and sustainability of the child care system reform outcomes.

Key Words: Child Care System Reform, Deinstitutionalization, Reintegration, Quality of Life, Children

აბსტრაქტი

სტატიაში დოკუმენტირებულია საქართველოში დიდი ზომის სახელმწიფო ინსტიტუციებიდან ბიოლოგიურ ოჯახებში რეინტეგრირებული ბავშვების ცხოვრების ხარისხის ზრდა. შეფასების შედეგები იმეორებს განვითარებულ ქვეყნებში ჩატარებული არაერთი კვლევის მიგნებას, რომლებიც ადასტურებს ბიოლოგიურ ოჯახში ბავშვის აღზრდის მნიშვნელობას და პრიორიტეტულობას.

კვლევა ეფუძნება თანამონაწილეობის პრინციპებისა და მომსახურების მიმღების ინდივიდუალური კრიტერიუმების გათვალისწინებით, მომსახურების შედეგების შეფასების პრინციპებს. ის არის ევროპისა და ცენტრალური აზიის ქვეყნებში სახელმწიფო ზრუნვაში მყოფი ბავშვების ცხოვრების ხარისხის შეფასების პირველ მცდელობას.

კვლევაში ჩართული იყო 224, 11-18 წლის ასაკის ყველა ბავშვს შემდეგი სამი ჯგუფიდან: ა) 2012 წელს საქართველოში არსებული, მზრუნველობამოკლებული ბავშვების ორი დიდი ზომის სახელმწიფო ინსტიტუციის ბინადრები; ბ) სახელმწიფო შემწეობისა და დონორული რესურსების გამოყენებით 2010-2012 წლებში რეინტეგრირებული ბავშვები; ბ) მხოლოდ სახელმწიფო შემწეობით 2010-2012 წლებში რეინტეგრირებული ბავშვები. გამოყენებული იყო ცხოვრების ხარისხის ინსტრუმენტი, რომელიც შემუშავებული იყო ამ კვლევისთვის, პირადი ცხოვრების პროტოკოლის საფუძველზე. კვლევა დაეფუძნა ნებაყოფლობითი მონაწილეობის და ინფორმირებული თანხმობის პრინციპებს.

რეინტეგრირებული ბავშვები უფრო ბედნიერად თვლიან თავს და მათი ცხოვრების ხარისხის მაჩვენებელი აღემატება ინსტიტუციებში მცხოვრები ბავშვების ცხოვრების ხარისხს. მაჩვენებელმა ინსტიტუციურ დაწესებულებებში შეადგინა 80%, ხოლო სახლში დაბრუნების შემდეგ გაიზარდა 88%-მდე. სტატისკიკურად მნიშვნელოვანი არ იყო სხვადასხვა მეთოდოლოგიით რეინტეგრირებულ ბავშვების ცხოვრების ხარისხის მაჩვენებლებს შორის განსხვავება, თუმცა ეს მაჩვენები უარყოფით კორელაციაში იყო ბავშვის რეინტეგრაციის ხანგრძლიობასთან.

კვლევის შედეგები კიდევ ერთხელ ადასტურებს ბავშვზე ბიოლოგიური გარემის დადებით გავლენას. ასევე თვალსაჩინოა რეინტეგრირებული ბავშვების და ბავშვზე ზრუნვის სხვა მომსახურებებში მცხოვრები ბავშვების ცხოვრების ხარისხის გრძელვადიანი შედეგების შეფასების მნიშვნელობა, რათა დადგინდეს საქართველოში ბავშვთა კეთილდღეობის სისტემის რეფორმის შედეგების მდგრადობა.

საკვანძო სიტყვები: ბავშვთა დაცვის სისტემის რეფორმა, დეინსტიტუციონალიზება, რეინტეგრაცია, ცხოვრების ხარისხი, ბავშვი

Introduction

Countries throughout the Central and Eastern Europe and Commonwealth of Independent States (CEE/CIS) including Georgia inherited the child care system predominantly based on institutional care, lacking other services on a continuum of care for children. According to UNICEF (2010) the ratio of children living in institutional care in this region is highest in the world and exceeds 1 per 100 children. In Georgia, after gaining the independence, a number of residents living in 46 state-run residential institutions was 5300 (1 per 200 children). 85% of those children had one or both parents and were placed in institutions mostly due to the economic reasons.

A negative impact of institutional care, affecting neurobiological, psychological and social aspects of child’s life are well explained and documented in the Attachment Theory and numerous studies (Bullock et al., 1993; Buote, 2006). One of the most influential theories that explain the negative effects of institutionalization on children’s health and development - Attachment Theory, developed by John Bowley in 1951 outlined the importance of enduring bond between a child and his/her primary caregiver. Many authors fount that, compared to the general population of children, those in large-scale residential care had more medical problems, non-organic failure to thrive and grow, cognitive delays, poor self-confidence, lack of empathy, anti-social behaviour, poor work prospects, higher probability of an autistic social personality, etc. (Curry, 1991). Longitudinal follow-up revealed that institutional deprivation was the most powerful predictor of individual differences in developmental outcomes. At the same time, some studies have demonstrated that children with deprived backgrounds can make a rapid recovery when they are placed in a caring family environment (Browne, 2005).

In the developed countries, especially the USA and the UK an opposition to institutionalization of children and adults, as well as deinstitutionalization process started in early 1950 and emphasised the negative consequences of institutional care compared to family-based care. At different levels of intensity and success, the countries of CEE/CIS Region started reforming of their child care systems and recognizing the importance of family-based care and de-institutionalization of childcare at the end of the 20th century (UNICEF, 2004).

The trend towards reforming child care system was introduced in Georgia after the collapse of the Soviet regime, which had opening up space for the modern ideas and approaches and a better recognition of child’s rights. More specific strategies of reforming the system have been on the agenda in the country since early 2000, when the Government of Georgia (GoG) committed to reorganizing child care system and has agreed on its guiding principles. At the early stage of the reform, its main priority was deinstitutionalization of child care institutions (Government of Georgia Action Plan on Child Protection and Deinstitutionalization 2005-2007). While the recognition of the importance of family strengthening, prevention and family based-care alternatives was documented by the state at the later stages of the reform (Government of Georgia Child Action Plan 2008-2011; Government of Georgia Child Care Reform Priorities 2011-2012).

At the outset of the reform, several external and internal forces were driving introduction of the reform strategies in Georgia. For example, the country has ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) in 1994, the implementation of which was monitored through submission of written Periodic Progress Reports to the U.N. Committee for the Rights of the Child. Georgia became a member of the Council of Europe (CoE), also advocating for the implementation of alternative care priorities as outlined in CoE Strategy for the Rights of the Child 2012-2015. Motivated to proceed on the road to the European Union accession, for Georgia the European Union was another major external motivator for the implementation of the Social and Child Welfare Reform measures and improving living conditions for institutionalized children (Transparency International Georgia, 2006).

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UN CRC), as well as many other international and Georgian regulations considers a biological family as the best environment for raising a child. Hence, the return of children into their families (reintegration) and prevention of a family separation were considered as the main priorities of the child care system reform in Georgia. At the same time, the state is responsible to intervene when child’s home is an unsafe environment or if in the process of deinstitutionalization, return into the biological family is not in the best interest of a child. For such cases GoG has ensured development of family substitute services, serving as alternatives to the large-scale residential institutions – foster care and small group homes.

According to the administrative data, in the process of reforming child care system 70% of deinstitutionalized children were placed into foster families and small group homes (SGH) or have graduated the state child care system due to their age.

The government has committed support to a family reunification process, ensuring assistance by a state social worker and monetary monthly support for each reintegrated child equalling to 90 GEL ($50) for a child without disabilities and 130 ($80) for a child with disabilities. In addition, selected biological families, deemed safe to take back children, but requiring additional assistance were supported using the Social Fund funded by the donor agencies (Greenberg and Partskhaladze, 2014). Social Fund was made available during the years 2012-2014 and ensured assistance of the NGO social workers, as well as minor refurbishments, purchase of basic furniture and appliances for the biological families. 30% of the children removed from the institutions had an opportunity to return into their families of origin with the state and other support.

Overall, out of 5300 children residing in large-scale institutions through Georgia at the initial stage of the reform, all but 109 children with disabilities (remained in two settings) were reintegrated into their biological families, placed in kinship and foster care or small group homes by December 2014. In May 2013 UNICEF Georgia reported that country had closed the last two institutions for children deprived of parental care with no disabilities, located in Kodjori and Telavi.

Literature Review

The child care system reform and almost full deinstitutionalization of the large-scale state child care settings implemented in Georgia, was considered as one of the most successful reforms in CEE/CIS. The backbone of the reform – development and strengthening of social work profession, introduction of a gatekeeping system, as well as alternative family substitute and family support services were also considered as notable achievements (UNICEF, 2015).

Despite an absolute undoubted priority of deinstitutionalizing child care system and positive developments achieved in Georgia, the attempts to generate the evidence about the outcomes of the reform and its impact on the engaged individuals are very limited. Controversy still exists about the positive and negative outcomes of the reform and deinstitutionalization process and its positive impact of the reforms can be easily undermined and discredited due the lack of the local scientific evidence; An administrative data about reintegrated children and children in the state and other residential care settings needs strengthening; this group is incomplete; Development of the state child and social protection policies and programs is poorly informed by the up-to-date local evidence.

In addition to the need for the local evidence, there is also a growing acceptance that children and young people should be more involved in evaluating and making decisions that affect them. This paradigm shift towards the participatory approach, originated in western countries, was triggered as a result of the children’s rights agenda exemplified by the UN CRC (Sinclair, 2004). An understanding that children should have active and not passive role in shaping social services, though needs further strengthening to some extend has already influenced policy makers in Georgia though need further strengthening (i.e. child recipients’ satisfaction is being included in the State Child Care Standards, etc.).

Another important theoretical advance of the past decades is the shift from evaluating outcomes against the universal definition of what contributes towards the quality care and service standards, towards the “individual’s conscious evaluative judgment of their quality of life by using person’s own criteria” (Diener et al., 1999). Although some agreement about the ‘good life’ components exist, individuals compare their objective living situation according to different internal values and standards and are likely to assign different weight to them. Hence, a unique individual criterion becomes increasingly more applied worldwide, overwhelming the common benchmarks. The measurement of subjective life satisfaction and quality of life became an important component of program evaluation and planning of individualized care in many western countries (Land and Michalos, 2012).

Analysis of the literature found considerable agreement regarding the life elements, or so called person-referenced core QoL domains contributing towards it. The most frequently suggested range of life domains, incorporating subjective and objective measures are as follows (Verdugo et al., 2005):

1. Emotional well-being: safety, stable and predictable environment, positive feedback.

2. Interpersonal relationships: affiliation, affection, intimacy, friendship, interaction.

3. Material well-being: ownership, possessions, employment.

4. Personal development: education and habilitation, purpose activities, assistive technology.

5. Physical well-being: health, care, mobility, wellness, nutrition.

6. Self-determination: choices, personal control, decisions, personal goal.

7. Social inclusion: natural support, integrated environment, participation.

8. Rights: privacy, ownership, due process, barrier free environment.

Proposed life domains are considered to be applicable across all stages of human development. However, determining the degree to which the quality of life and satisfaction with individual life domains are similarly or differently perceived by individuals across stages of development is still being debated. Studies, measuring satisfaction of adults with their QoL have received considerable attention over the last two decades and have generated important findings, widely used in the fields of healthcare, social protection, etc. On the contrary, this topic has received less attention with regards to children and adolescents (Gadermann et al., 2010). It has been suggested that this situation is related to the fact that instruments for assessing QoL children have been developed relatively recently and are not adapted to the cultural context, developmental stage, life circumstances and other characteristics of the different groups of children, hence, need further strengthening.

Research Methodology and Findings

The study used quantitative methods in the form of checklists and closed and open ended questions. By using a simple static comparison, it aimed to define if QoL measures differ between children in the institutions and children reintegrated using two different methodologies.

Instruments: The research instrument used for this study was developed for this particular assessment and was applied for the first time. The instrument was based on the Personal Life Quality Protocol introduced by Prof. James Conroy (Centre for Outcome Analysis, 2001). It was adapted to the characteristics of a child population with the experience of living in the state care in Georgia. Detailed literature review could not identify other instruments better meeting needs of this project.

The instrument assesses subjective satisfaction of a child with the quality of life domains outlined in the existing QoL literature and relevant to the institutional and family context of the assessed children. By rating the level of their satisfaction on the 20 items, children identified their self-perceived level of happiness by using their own criteria. The reliability of this approach with children in non-family placement, and with people with intellectual disabilities in residential settings in the USA, has been widely studied and supported by the author of the Personal Life Quality Protocol and other scholars (Conroy et al., 1987).

Two sets of questionnaires were used with different groups covered by the research. The complete version of the questionnaire, including over 84 closed and open ended questions was used with children residing in Telavi and Kodjori institutions. Due to the time constraints and a large scope of the assessment of reintegrated children, two groups of children reunified with their biological families were assessed using simplified questionnaire including 40 closed ended questions with answers given on scales or numbered. The tool was used with children of the age 11-18 years, able to comprehend its content.

Participants: The study population consisted of the three groups of children. The first group represented all 33 children of the age 11-18 years, remaining in two large-scale residential institutions for children of the age 6-18 years deprived of parental care still existing in Georgia in 2012. Similar settings were abolished in the frames of the child care system reform in Georgia in 2013. Telavi and Kodjori institutions, as well as children assessed there should be considered to be representative of all other institutions for the same target group, as the state settings applied standardized criteria for the assessment, enrolment, care and discharge of children, as well as the same national care standards.

The second group was comprised of 119 children reintegrated with their 93 families during the years 2011-2012. This group represented all 11-18 old children, out of 155 reintegrated during that time-frame through the state reintegration program, coupled with the Social Fund support. Previous place of their residence were different state institutions, with the characteristics similar to Kodjori and Telavi settings. As noted above, this group of children received the state reintegration benefit (monetary support and social work services), as well as an additional assistance in the form of minor refurbishments, purchase of basic furniture and appliance from the Social Fund resources, etc. Very importantly, the families and children in this group were additionally assessed, supported and monitored by the social workers from the designated non-governmental organization Save the Children.

The third assessed group consisted of all 70 children of the age 11-18 years, out of 151 reintegrated during 2010-2012. Different from group two, these children were reunified with their families without receiving the Social Fund support. Similarly to the group one and group two, the lived in the large-scale residential institutions for children of the age 6-18 years deprived of parental care.

Overall, children included in the second and third groups represented the full population of children of this age group reintegrated in the country in the given period.

Procedures: Interviews with the children were conducted in Kodjori and Telavi institutions (group one) or their homes through Georgia (group two and three) in private. The lead researcher and other interviewers had undergraduate or graduate degrees in social work. The interviewers received training by a lead researcher, discussing interviewing techniques and etiquette, handling challenging situations and questions. They were requested to rephrase questions to in order to ensure a full understanding, but not to lead the child toward any specific answer. To help the younger children understand the Likert scales used in a questionnaire, a response sheet with five faces expressing great happiness, happiness, no emotion, unhappiness and crying was shown to the children in need of such support. For the more mature children, the five point scales were explained and read out loud.

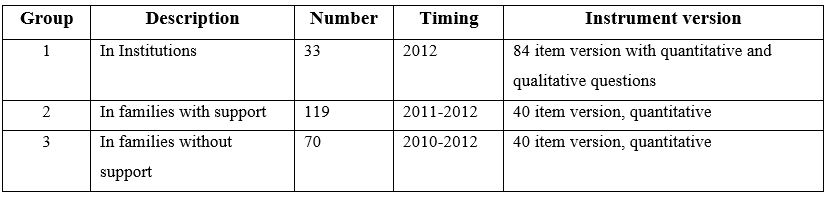

Group Description Number Timing Instrument version

1 In Institutions 33 2012 84 item version with quantitative and qualitative questions

2 In families with support 119 2011-2012 40 item version, quantitative

3 In families without support 70 2010-2012 40 item version, quantitative

The study adhered to the principle of voluntary participation and informed consent. Participants of the study have signed an informed consent form.

Results: The data-entry and processing was performed using the SPSS 17.0 version and yielded the following findings:

Demographics of children in Telavi and Kodjori institutions at the time of the assessment:

• Average age – 14,5 years

• Girls - 39%, boys - 61%

• Average length of stay in formal care – 6 years

• 91% of the children were Georgian. Other children were of Azeri, Ossetian, and other origin

• More than 50% of children considered to be places in the institutional care due to the family crisis and hard economic conditions.

Data about the needs of reintegrated children was enriched with the findings of a study conducted by the Save the Children with the same children. The Needs Assessment of Reintegrated Children in Georgia report provided an in-depth quantitative data about this group of children and their families, revealing that reintegrated families represent a vulnerable group, characterized by the lack of financial, psycho-emotional, intellectual and life resources, and require multifaceted assistance in order to ensure the long-term well-being of reunified children (UNICEF, 2013).

Demographic data of the two groups of reintegrated children were as follows:

• Average age – 14

• Girls - 45%, boys - 55%

• Average length of stay in formal care was 6 years for children reintegrated with the additional Social Fund support (group 2), versus 4.5 years for the other group reintegrated only with the state support (group 3).

• 91% of the children in the group 2 were Georgian, while this number equalled to 86% in the group 3.

• 46 % of children were places in the institutions due to the family crisis and hard economic conditions.

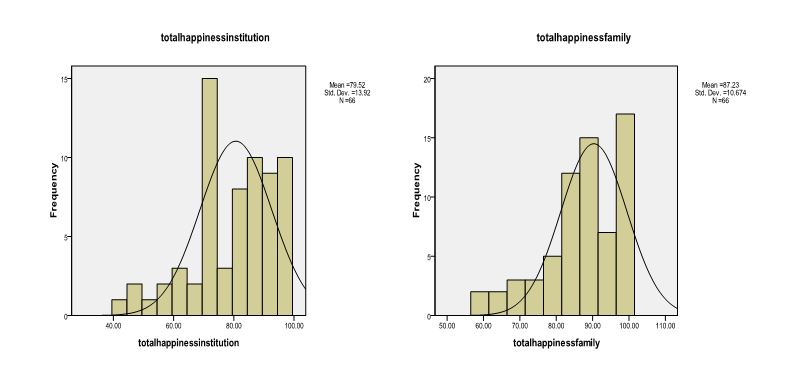

Analysis of the findings revealed statistically significant difference between the quality of life of children living in the large-scale residential institutions and in the family environment. On average, QoL increased from 80% in institutions to 88% in families (Z=-3.83, p<0.0001). Association between the variable revealed that children of both sex were equally happy after returning home. A negative correlation was found between the length of stay in the institution and QoL score after the return. Children who have spent 0-24 month in the institutions were happier after returning home, than children institutionalized for 24-60 months (X2=12.828, p=0.012). However, QoL was not affected with the length of institutionalization over 60 months. Age of a child was not correlated with QoL in the institution, while it was negatively correlated with QoL after the reintegration (younger children feel happier when retuned home). Overall tendency of reducing QoL with the length of reintegration was characteristic to both groups returned home. Though, these scores were still significantly higher that QoL in the institutions.

Association between other variable will be determined after the completion of the third ongoing stage of the research, assessing long-term outcomes of reintegrated children. Additional correlations requiring attention are: a frequency of visitations in the institutions and children’s QoL in these settings, the extend of collaboration between a child and a social workers and QoL of a child in the institution and after the reintegration, etc.

The study had a number of limitations, related to the sample size, as well as shortcomings in satisfaction research in general. Even though all three samples covered almost 100% of the population with similar characteristics and are representative of the relevant groups, their relatively small size may impact the generalization and associations found between variables. Due to the fact that as a result of the deinstitutionalization process, all large-scale state residential institutions for children deprived of parental care were closed, no additional studies of this group of children are feasible in Georgia. However, further studies of QoL children placed in other residential settings in Georgia or abroad, as well as reintegrated children can reveal additional findings and determine if the same associations are found in a larger sample size.

Due to the time and resource constrains, samples of reintegrated children were assessed using a short version of the instrument, not including questions about children’s collaboration with social workers, their role in elaborating individual development plans and overall participation in determining their future. It was also not possible to conduct pre- and post-assessments of QoL reintegrated children during their enrolment in the institutions.

In addition, this study, as well as other assessments of satisfaction and QoL could have been constrained with the respondents' desire to provide answers acceptable for their peers and a society, memory or comprehension difficulties, and response biases such as acquiescence and recency (Conroy and Wilson, 2002).

Discussion

The study of the quality of life of children with the experience of living in the state care demonstrated that overall children are happier in their biological families, compared to the large-scale residential institutions. Despite the widespread assumption among the criticists of deinstitutionalization of the child care system, that children from the poor families could be better-off in out-of-home settings, a child satisfaction with the life with parents was not affected by the difficult economic and social conditions present in these families. These findings urge to further emphasise strengthening of gatekeeping and family strengthening services and ensure that no child is separated from a safe family environment.

Analysis of the QoL domains assessed as individual items, as well as a multidimensional indicator for each child, reveal that self-perceived ability of children to relate with their friends, siblings parents and relatives is significantly higher is a family environment; children have a stronger sense of security and privacy and an ability to participate in decision making processes; they believe that attitudes of other people towards them is better when living at home. However, oftentimes children’s physical living environment, ability to pursue education and other domains strongly linked with the need of an infrastructure and formal systems, exhibit more limited increase in score (and occasionally, ever its reduction).

Children living at home have a better knowledge of their social workers. On the other hand, children residing in the institutions have limited knowledge of social workers. In most of the cases they report limited participation in the making decisions processes and development of the individual development plans. Findings reveal that the state systems failed to explain and extend social work support to them.

In conclusion, it is possible to argue that the preventing separation of children from their families and support to their reintegration should be a priority for the state child care system, as children perceive families as the best environment ensuring higher quality of life.

References

1. Browne, K. (2005). A European Survey of the Number and Characteristics of Children Less than Three Years Old in Residential Care at Risk of Harm. Adoption & Fostering December 2005 Vol. 29 no. 4 23-33

2. Bullock, R., Little, M., and Millham, S. (1993). Residential Care for Children. A Review of the Research. HMSO.

3. Buote, D. (2006). The Power of Connection: The Relation between Attachment and Resilience in a Sample of High Risk Adolescents. Doctoral Thesis. University if British Columbia

4. Conroy, J. and Wilson, L. (2002). Satisfaction of 1,100 Children in Out-of-Home Care, Primarily Family Foster Care, in Illinois' Child Welfare System." Retrieved on May 2012 from http://www.eoutcome.org/Uploads/COAUploads/PdfUpload/SatisfactionInIllinoisChildWelfare.pdf

5. Conroy, J., Walsh, R. and Feinstein, C. (1987). Consumer Satisfaction: People with Mental Retardation Moving from Institutions to the Community. In S. Breuning & R. Gable (Eds.). Advances in Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities, Volume 3 (pp. 135-150). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

6. Curry, J. F. (1991). Outcome Research on Residential Treatment: Implications and Suggested Directions. American Orthopsychiatric Association 61(3)

7. Diener, Ed, E. M. Suh, R. E. Lucas, and H. L. Smith (1999). Subjective Well-Being: Three Decades of Progress. Psychological Bulletin. Vol. 125, No. 2, 276-302

8. Gadermann, A.M., Schonert-Reichl, K.A. & Zumbo, B.D. Soc Indic Res (2010). Investigating Validity Evidence of the Satisfaction with Life Scale Adapted for Children. Social Indicators Research. April 2010, Volume 96, Issue 2, pp 229–247

9. Government of Georgia Action Plan on Child Protection and Deinstitutionalization 2005-2007

10. Government of Georgia Child Action Plan 2008-2011.

11. Government of Georgia Child Care Reform Priorities 2011-2012

12. Greenberg, A. and Partskhaladze, N. (2014). How the Republic of Georgia has nearly Eliminated the Use of Institutional Care for Children. Infant Mental Health Journal. Vol. 35, Issue 2, pg 185-191

13. Land, K. and Michalos, A. (2012). Handbook of Social Indicators and Quality of Life Research. Springer

14. Personal Life Quality Protocol (2001). Center for Outcome Analysis. Retrieved October 2011 from http://www.eoutcome.org/default.aspx?pg=327

15. Sinclair R. (2004). Participation in Practice: Making it Meaningful, Effective and Sustainable. Children and Society. Vol. 18, pp. 106-118

16. Transparency International Georgia (2006). Social Protection System reform in Georgia. Report.

17. UNICEF (2004). Lessons learned from social welfare system reform and some planning tips. Regional Office for Central and Eastern Europe, the Commonwealth of Independent States (CEE/CIS) and Baltic States: Occasional Paper from Child Protection Series.

18. UNICEF (2010). At home or in a home? Formal care and adoption of children in Eastern Europe and Central Asia.

19. UNICEF (2013). Needs Assessment of Reintegrated Children in Georgia. Study Report. Retrieved on May 2014 from http://unicef.ge/uploads/Needs_Assessment_of_Reintegrated_Families_in_Georgia-Report-eng.pdf

20. UNICEF (2015). Evaluation of Results Achieved through Child Care System Reform 2005-2012 in Georgia. Pluriconsult Evaluation Report

21. Verdugo, M. A, Schalock, R. L, Keith, K. D and Stancliffe, R. J. (2005). Quality of Life and its Measurement: Important Principles and Guidelines. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. Volume 49 Part 10 pp 707-717, October 2005. Blackwell Publishing Ltd